For most Americans, generic drugs are the only way to afford chronic medications. You take lisinopril for blood pressure, metformin for diabetes, or atorvastatin for cholesterol - and you expect it to cost a few dollars a month. But what you pay at the pharmacy counter isn’t random. It’s shaped by a web of federal rules, rebate systems, and market forces you rarely see. The government doesn’t set generic drug prices directly like it does in Canada or Germany. Instead, it uses a mix of rebates, program rules, and indirect pressure to keep costs down. Here’s how it actually works - and why your $4 copay might suddenly jump to $45.

The Medicaid Rebate System: The Hidden Engine Behind Low Prices

Most people don’t realize that Medicaid is the biggest driver of low generic drug prices in the U.S. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), every drug manufacturer - including those making generics - must pay rebates to states for every prescription filled by a Medicaid patient. The formula is strict: the rebate is the greater of 23.1% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP), or the difference between AMP and the lowest price the company offers any other buyer.

This isn’t a suggestion. It’s the law, written into 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(c)(2). Manufacturers report AMP and Best Price to CMS every quarter. In 2024, these rebates totaled $14.3 billion - 78% of all Medicaid drug rebates - and nearly all of that came from generics. That’s why pharmacies can afford to sell a 30-day supply of generic metformin for $4. The rebate covers the difference between what the pharmacy pays the wholesaler and what the patient pays. Without this system, most generic prices would be 2-3 times higher.

Medicare Part D and the $2,000 Cap

Medicare Part D doesn’t negotiate generic prices directly - not yet. But it does control how much beneficiaries pay out of pocket. Starting in 2025, the Inflation Reduction Act capped annual out-of-pocket spending on Part D drugs at $2,000. That’s a big deal for people taking multiple generics. Before, someone on five different generics could hit $5,000 in annual costs before catastrophic coverage kicked in. Now, they stop paying after $2,000.

Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) beneficiaries pay even less: $0 to $4.90 per generic prescription. Compare that to brand-name drugs, where the same group pays up to $12.15. The gap exists because generics are cheaper to begin with - and the rebate system works harder for them. CMS data shows that in 2024, the average Medicare beneficiary spent $327 per year on generics, down from $412 in 2022. That drop came mostly from the IRA’s out-of-pocket cap, not price cuts from manufacturers.

How the 340B Program Keeps Drugs Affordable for the Poor

If you get care at a community health center, a safety-net hospital, or a clinic serving low-income patients, you’re likely benefiting from the 340B Drug Pricing Program. This program requires drugmakers to sell outpatient medications - including generics - at steep discounts to qualifying providers. Discounts range from 20% to 50% below the average market price.

These savings aren’t just numbers. A 2025 survey from the Community Health Center Association found that 87% of clinics saw improved patient adherence to medications after switching to 340B-priced generics. One clinic in Detroit reported that after implementing 340B for metformin, diabetes-related ER visits dropped by 31% in six months. But here’s the catch: 340B doesn’t lower prices at your local CVS. It only applies to specific providers. If you’re not enrolled in one of those programs, you won’t see this discount - even if you’re poor.

Why Some Generic Prices Go Wild

Not all generics are created equal. When a drug has only one or two manufacturers, prices can spike. Take pyrimethamine (Daraprim), used to treat rare parasitic infections. In 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals raised the price from $13.50 to $750 per pill. After public outrage, generic versions entered the market - but by 2024, only two companies were making it. The price jumped 300% in just two years. Why? No competition. No buyers. No pressure.

This happens more often than you think. The FDA approves over 1,200 generic drugs every year, but many are for small markets - orphan drugs, older antibiotics, or niche treatments. If only one company can make it profitably, they control the price. The government doesn’t step in to cap it. The market is supposed to fix it - but when there’s no market, there’s no fix.

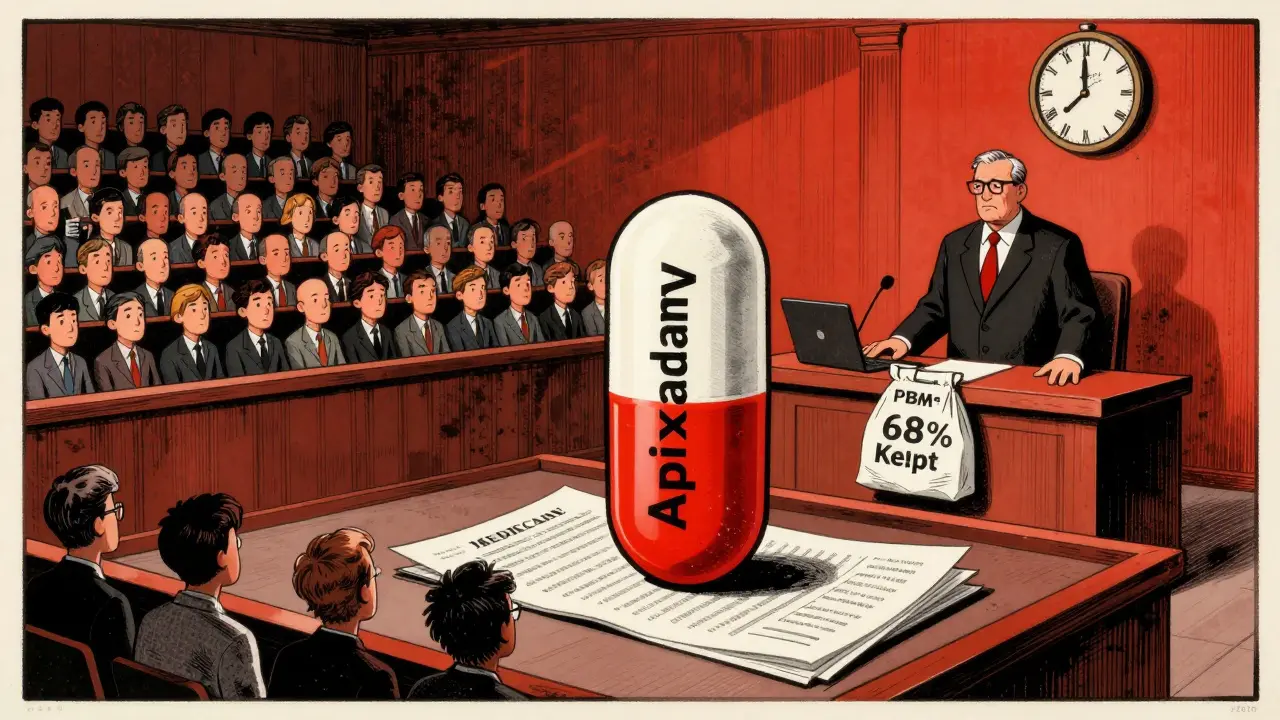

Who’s Really Making Money? The PBM Problem

When you think of drug pricing, you think of manufacturers and pharmacies. But the real middlemen are pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) - companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. They negotiate rebates with drugmakers on behalf of insurance plans. The problem? Those rebates don’t always go to you.

A July 2025 Senate HELP Committee report found that 68% of the savings from generic drug rebates never reach the patient. Instead, PBMs keep them as profit or use them to lower premiums for big employers. You might see a $5 copay on your generic, but the PBM collected $12 in rebates from the manufacturer. That’s why your plan says it’s saving you money - but your out-of-pocket bill doesn’t reflect it.

What’s Changing in 2026 and Beyond

The biggest shift is coming with Medicare drug price negotiations. The Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare negotiate prices for high-cost drugs starting in 2026. But generics are mostly exempt - unless they’re the only version available. In 2027, CMS will negotiate prices for generic versions of apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto), two blood thinners with over 5 million Medicare users. These aren’t new drugs. They’re off-patent generics. But because they’re so widely used, they’re now targets.

Analysts predict prices could drop 25-35% on these two drugs alone. That’s $40.7 billion in annual spending being renegotiated. It’s the first time Medicare will directly pressure generic prices - not through rebates, but through direct negotiation. If it works, more generics could be added in future years.

Why the U.S. System Works - and Why It Doesn’t

The U.S. has the fastest generic approval rate in the world. Over 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics - compared to 65% in Europe. That’s because the FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan has cut approval times for complex generics by 37% since 2017. When a brand drug loses patent protection, generics flood the market within months.

But speed doesn’t mean fairness. The U.S. pays 1.3 times more for generics than other OECD countries, according to a 2025 KFF analysis. Why? No centralized buyer. No price benchmarking. No national negotiation. We rely on competition - but competition only works when there’s more than one player. When there’s one, prices rise. When there’s none, patients go without.

What You Can Do

Don’t just accept your copay. Check your plan’s formulary tier. Some plans put certain generics in higher tiers, even if they’re chemically identical. Use the Medicare Plan Finder tool - 48 million people did in 2024 - to compare plans based on your exact medications. Ask your pharmacist if there’s a cheaper alternative. Some generics from different manufacturers cost 50% more even though they’re the same drug.

If you’re on Medicare and pay over $2,000 a year on meds, you’re already protected. If you’re not, look into Medicaid or 340B clinics. And if you’re hit with a surprise $50 bill for a generic you’ve taken for years - call your insurer. That’s not normal. It’s likely a PBM glitch, a formulary change, or a supplier switch. You have the right to ask why.

Duncan Careless

December 29, 2025 AT 19:19Man, I never realized Medicaid rebates were keeping my metformin at $4. Thought it was just magic. Guess the system works better than we give it credit for - even if it’s a mess.

Samar Khan

December 30, 2025 AT 10:33PBMs are literally stealing from us 😭💸 68% of rebates? That’s not a business model, that’s a heist. And they wonder why people hate healthcare? 🤬

Russell Thomas

December 30, 2025 AT 20:21Oh wow, so the government doesn’t set prices… but somehow magically keeps them low? 😂 Let me guess - the same government that lets pharma charge $750 for a pill that used to cost $13.50? Yeah, real ‘market-driven’ here. Classic American capitalism: let the poor choke on the fine print while the middlemen cash in. 🙃

Joe Kwon

January 1, 2026 AT 05:40From a policy design standpoint, the Medicaid rebate + 340B + Part D cap combo is actually a clever patchwork solution to a broken system. It’s not ideal, but it’s functional at scale - especially given the lack of centralized negotiation. The real failure is structural: we rely on volume-based rebates instead of value-based pricing. That’s why generics stay cheap *unless* market concentration kicks in. The 2027 apixaban negotiation is the first real step toward systemic correction. If CMS can negotiate a 30% drop on a generic, it sets a precedent for future candidates. The PBM opacity is the elephant in the room though - transparency mandates are long overdue.

Nicole K.

January 1, 2026 AT 15:30If you’re paying more than $5 for a generic, you’re just lazy. Stop being a victim and get on Medicaid. It’s not that hard.

Fabian Riewe

January 3, 2026 AT 11:02Big shoutout to the 340B clinics - they’re doing God’s work. My cousin in rural Alabama gets her insulin for $3 because of one. And yeah, PBMs are sketchy, but at least someone’s trying to make this work. Keep pushing for more transparency, but don’t throw the whole system out. We’re closer than you think.

Greg Quinn

January 4, 2026 AT 09:57It’s fascinating how we’ve engineered a system that makes drugs affordable through indirect coercion rather than direct control. We don’t say ‘this is fair,’ we say ‘here’s a rebate if you comply.’ It’s capitalism with a moral veneer. And yet - it works. For most people, most of the time. But when it breaks - when there’s one manufacturer, one buyer, one monopoly - the system collapses. We’re not fixing the flaw. We’re just hoping the flaw doesn’t hit you. That’s not policy. That’s luck.

Lisa Dore

January 4, 2026 AT 19:52Hey everyone - if you’re struggling with drug costs, DM me. I work at a community clinic and can help you find 340B providers near you. No judgment. No paperwork nightmares. Just real help. You’re not alone 💪❤️

Sharleen Luciano

January 5, 2026 AT 22:47It’s amusing how people act surprised that the U.S. healthcare system is a disaster. You don’t get to have a free market in essential medicines and then cry when the market fails. This isn’t ‘innovation’ - it’s exploitation dressed up as economics. Anyone who thinks this is ‘working’ is either on the payroll or hasn’t read the fine print. The IRA’s negotiation clause is the only thing that even remotely resembles justice - and it’s too little, too late.