When a new drug hits the market, the first patent protecting its active ingredient usually lasts 20 years. But that’s not the end of the story. Many blockbuster drugs stay off-limits to generics for decades-not because of one patent, but because of dozens of secondary patents. These aren’t about the medicine itself. They’re about how it’s made, how it’s taken, or what it’s used for. And they’re the main reason why some drugs cost hundreds of times more than they should.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

Secondary patents don’t protect the chemical that makes a drug work. That’s the job of the primary patent. Instead, they cover everything else: the shape of the pill, the way it releases medicine over time, the specific crystal form of the ingredient, or even a new disease it can treat. Think of it like buying a car. The primary patent is the engine. The secondary patents are the leather seats, the GPS system, the color, and the extended warranty. The most common types include:- Formulation patents: Protect how the drug is delivered-slow-release pills, liquids, patches. AstraZeneca’s Nexium was a switch from Prilosec’s mix of two molecules to just one (esomeprazole). That tiny change earned them nearly 8 extra years of exclusivity.

- Method-of-use patents: Claim a new use for an old drug. Thalidomide was originally a sleep aid. Later, it got patents for treating leprosy and multiple myeloma. Each new use meant a new patent clock.

- Polymorph patents: Protect different crystal structures of the same molecule. GlaxoSmithKline’s Paxil used this to block generics for years after the main patent expired.

- Combination patents: Bundle two drugs together. This is common in HIV and cancer treatments.

Some companies file over 100 secondary patents on a single drug. Drug Patent Watch found that AbbVie’s Humira had 264 secondary patents, stretching its monopoly until 2023-even though the original patent expired in 2016.

Why Do Companies Use Them?

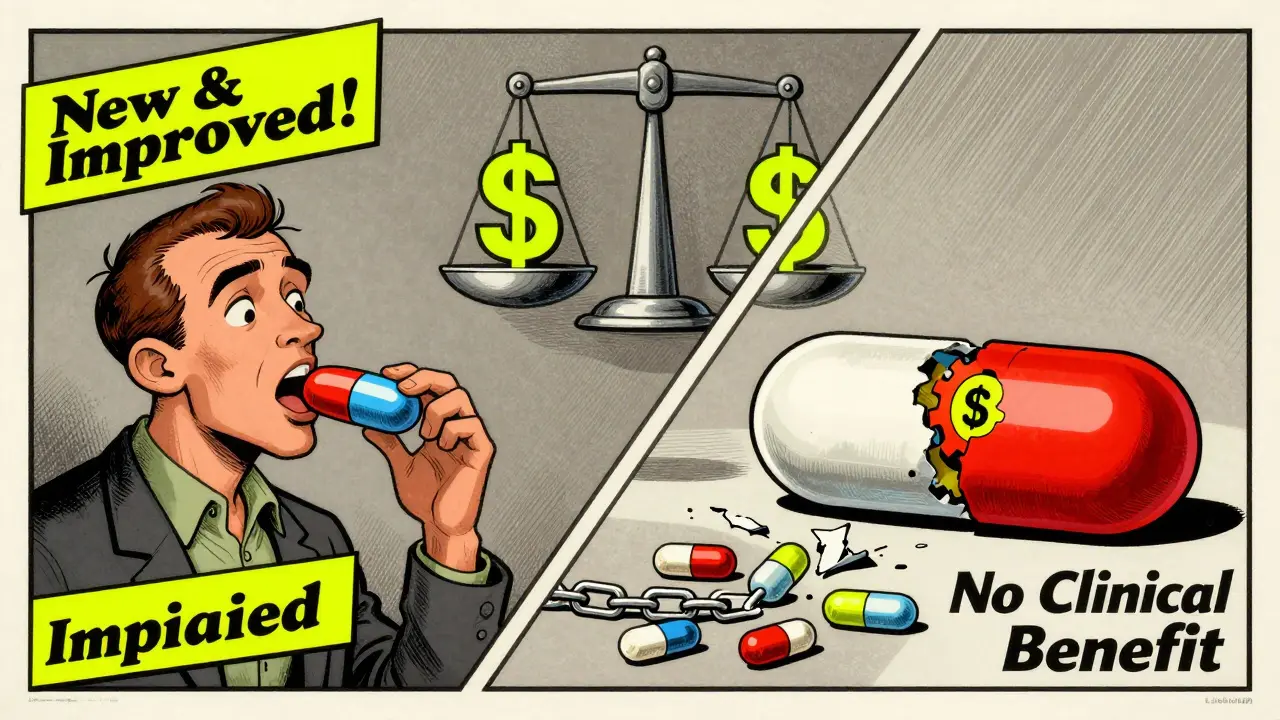

It’s simple: money. A single drug can earn $1 billion a year. Losing that to generics means losing 80% of revenue overnight. Secondary patents delay that drop. According to a 2019 Health Affairs study, drugs with secondary patents see generic entry delayed by an average of 2.3 years. For a top-selling drug, that’s billions in extra revenue. The strategy is called pharmaceutical lifecycle management. Companies start planning secondary patents 5 to 7 years before the main patent runs out. They file formulation patents 3-4 years before expiry, and method-of-use patents after approval. Then they push the new version to doctors and patients-often right before generics become available. This tactic, called product hopping, tricks people into switching to the newer, pricier version. A California doctor told Medscape in 2022 that reps regularly show up with new pills, new dosages, new packaging-just before generics hit. Patients don’t always know the old version works just as well. Pharmacies and insurers pay more, and patients end up with higher copays.Who Pays the Price?

The cost isn’t just financial. It’s human. In the U.S., Humira cost $20 billion a year at its peak. With generics, that could’ve dropped by 80%. Instead, patients paid more, insurers paid more, and Medicare paid more. Generic manufacturers say navigating these patent thickets adds $15-20 million in legal costs per drug and delays entry by over 3 years. But it’s not all bad. Some secondary patents bring real benefits. New formulations reduced side effects by 37% in some chemotherapy drugs, according to the American Cancer Society. Better dosing schedules mean fewer pills a day. That helps people stick to their treatment. The problem isn’t innovation-it’s how much is real innovation versus how much is just legal maneuvering. A 2016 Harvard study found only 12% of secondary patents led to meaningful clinical improvements. The rest? Just extensions.

Global Differences: Where It’s Allowed and Where It’s Blocked

Not every country lets companies play this game. India’s patent law, Section 3(d), says you can’t patent a new form of an old drug unless it’s significantly more effective. That’s why Novartis lost its fight to patent a new version of Gleevec in 2013. India’s generics industry exploded after that, making life-saving drugs affordable worldwide. Brazil requires health ministry approval before a patent can be enforced. The European Union asks for proof of “significant clinical benefit” for some secondary patents. The U.S.? No such requirement. That’s why 89% of drugs earning over $1 billion a year have 10 or more secondary patents-compared to just 22% of drugs under $100 million. The UN Development Programme called this a global access issue. In 68 low- and middle-income countries, secondary patents are the biggest legal barrier to affordable medicines.How Are Generics Fighting Back?

Generic companies don’t sit still. They file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification-essentially saying, “Your patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it.” In 2022, 92% of listed secondary patents got challenged. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded in court. Why so low? Because the system is stacked. Filing a challenge costs millions. Most generics can’t afford to fight 10 patents at once. Big pharma uses the threat of lawsuits to scare them off. Still, some are winning. In 2023, the Federal Circuit limited how broad antibody patents could be. That’s a sign courts are starting to crack down. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare new power to challenge certain secondary patents. The European Commission’s 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy targets “patent thickets” directly.What’s Next?

The tide is turning-but slowly. Analysts predict secondary patent filings will keep rising, but with more scrutiny. By 2027, companies may need to prove real clinical value to keep their patents. Investors are getting nervous. Politicians are talking. Patients are demanding change. The future of drug pricing depends on this. If secondary patents stay unchecked, we’ll keep paying premium prices for minor tweaks. If courts and regulators start demanding real innovation, we’ll get better drugs faster-and cheaper. It’s not about stopping innovation. It’s about stopping abuse.

Real-World Examples

- Humira (Adalimumab): 264 secondary patents. Blocked generics until 2023. Cost: $20 billion/year.

- Nexium (Esomeprazole): Switched from Prilosec’s racemic mix to a single enantiomer. Added 8 years of exclusivity.

- Paxil (Paroxetine): Polymorph patent delayed generics for 4 years after primary patent expired.

- Gleevec (Imatinib): Novartis tried to patent a new crystal form in India. Denied under Section 3(d). Generic versions flooded the market.

These aren’t outliers. They’re standard practice.

How to Spot a Secondary Patent Play

If you’re a patient, caregiver, or even a policymaker, here’s how to tell when a company is stretching patents instead of improving medicine:- A drug gets a new version right before generics launch.

- The new version has the same active ingredient, just a different pill shape or release speed.

- The marketing focuses on “improved convenience,” not better outcomes.

- The price jumps 20-50% with no change in effectiveness.

- The old version is suddenly harder to find.

That’s not innovation. That’s a legal tactic.

Are secondary patents legal?

Yes, in most countries-including the U.S., Canada, and much of Europe. But they’re heavily restricted in places like India and Brazil, where laws require proof of real therapeutic improvement. The legality doesn’t mean they’re ethical or beneficial for public health.

Do secondary patents help patients?

Sometimes. A few lead to better dosing, fewer side effects, or new uses for old drugs. But studies show only about 12% of secondary patents deliver meaningful clinical benefits. Most are minor changes designed to delay generics, not improve care.

How long do secondary patents last?

They last 20 years from their own filing date-not from the original drug approval. Since many are filed years after the primary patent, they can add 4-11 extra years of exclusivity. For drugs without strong primary patents, secondary patents can extend protection by nearly a decade beyond normal data exclusivity.

Why don’t regulators block them?

In the U.S., the FDA doesn’t judge the quality of patents. It only lists them in the Orange Book if they meet basic criteria. The patent office grants them based on legal standards, not medical value. That means a patent can be approved even if the change is trivial-like switching from a capsule to a tablet.

Can I tell if a drug is protected by secondary patents?

You can check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists patents for branded drugs. But not all patents are listed-some are kept secret as “reserve” patents. If a drug has multiple versions on the market, or if a new version appears right before generics launch, secondary patents are likely involved.

What Can Be Done?

Change is coming-but it needs pressure. Here’s what’s already happening:- Medicare can now challenge certain secondary patents under the Inflation Reduction Act.

- India and Brazil block low-value patents outright.

- Courts are tightening obviousness standards, especially for chemical tweaks.

- Generic manufacturers are teaming up to share legal costs.

What’s next? Stronger patent review standards. Public disclosure of all patents. Penalties for “product hopping.” And maybe, just maybe, a system that rewards real innovation-not legal loopholes.

For now, the system still favors the companies that file the most patents-not the ones that make the best medicine.

Shane McGriff

January 20, 2026 AT 08:02Wow. This is one of the most clear-eyed breakdowns of pharma’s game I’ve ever read. I’ve been on Humira for years and had no idea they were stacking patents like Jenga blocks. The fact that 89% of billion-dollar drugs have 10+ secondary patents? That’s not innovation-that’s exploitation. Thanks for laying it out like this.

thomas wall

January 22, 2026 AT 01:11It is deeply troubling, and frankly immoral, that a system designed to incentivize innovation has been perverted into a mechanism for corporate rent-seeking. The very notion that a change in pill shape can extend a monopoly for nearly a decade is not merely legal-it is an affront to public health ethics. We are not merely overpaying; we are subsidizing deception.

Thomas Varner

January 23, 2026 AT 06:29...so like... they just keep filing patents on the same drug until the generics give up? That’s wild. I mean, I get that companies want to make money, but this feels like playing Monopoly with real people’s lives. And why does the FDA just sit there and list them all? No checks? No balance? Just... yeah, sure, patent #264, here you go.

clifford hoang

January 23, 2026 AT 12:57THIS IS A COORDINATED ATTACK BY THE BILDERBERG GROUP AND THE FEDERAL RESERVE TO CONTROL THE POPULATION THROUGH MEDICINE PRICING. THEY USE PATENTS LIKE A WEAPON. WHY DO YOU THINK THEY BLOCKED GLEEVEC IN INDIA? BECAUSE THEY WANT YOU TO BE DEPENDENT. THE REAL DRUG ISN’T ADALIMUMAB-IT’S FEAR. THEY’RE SELLING YOU SUFFERING AND CALLING IT ‘INNOVATION’. 🤡💊 #PharmaCult

Edith Brederode

January 25, 2026 AT 11:10This made me cry. My mom couldn’t afford her chemo because of this. We had to switch to a cheaper version that gave her worse side effects. I just wish people realized these aren’t ‘business decisions’-they’re life-or-death choices for real families. ❤️

Arlene Mathison

January 25, 2026 AT 17:23Okay but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater-some of these secondary patents actually HELPED people! Like the slow-release versions that mean you don’t have to take 5 pills a day? That’s huge for elderly patients. It’s not ALL bad. We just need better rules-not a blanket ban.

Emily Leigh

January 26, 2026 AT 15:35so... like... the whole thing is just a scam? i mean, i knew big pharma was shady but this is next level. why are we even pretending this is about science? they’re just patent lawyers with lab coats. 🙄

Crystal August

January 27, 2026 AT 09:50You people are naive. This isn’t about ‘ethics’-it’s about capitalism. If you think companies are supposed to be ‘fair’, you’ve never opened a business. They’re not evil-they’re just doing what every business does: maximize profit. Stop acting like they owe you cheap medicine. You want it cheaper? Pay more taxes. Or move to India.

Andy Thompson

January 27, 2026 AT 19:39THEY’RE DOING THIS BECAUSE THE GOVERNMENT IS IN BED WITH BIG PHARMA. I SAW A VIDEO ON TIKTOK WHERE A FORMER FDA EMPLOYEE SAID THEY’RE PAID TO LOOK THE OTHER WAY. IT’S ALL A LIE. THEY WANT YOU TO BE SICK. THAT’S WHY THEY DON’T CURE CANCER. THEY MAKE MORE MONEY WHEN YOU’RE CHRONIC. 🚨💉 #BigPharmaCoverUp

Art Gar

January 29, 2026 AT 17:15It is axiomatic that intellectual property rights, as codified under Title 35 of the United States Code, serve the constitutional mandate to ‘promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.’ The invocation of ‘abuse’ in this context constitutes a rhetorical fallacy, conflating legal permissibility with moral desirability. The existence of secondary patents does not, ipso facto, constitute a violation of public welfare. One must distinguish between regulatory oversight and normative judgment.

Nadia Watson

January 30, 2026 AT 20:04Interesting read. I'm from Kenya and we see this every day-people paying 10x for drugs because generics can't get through the patent maze. In my village, someone dies every month because they can't afford the ‘new version’ of a drug that’s been around for 20 years. The U.S. isn't just broken-it's exporting this harm. We need global reform, not just local fixes.

Jacob Cathro

January 31, 2026 AT 17:19so like... patent thickets? lol. that’s just corporate jargon for ‘we filed 200 dumb patents so you can’t compete’. it’s not innovation, it’s legal terrorism. and the FDA? they’re just the bouncer at the club letting all the rich guys in. 🤡💸 #PharmaScam

Courtney Carra

February 1, 2026 AT 08:12It’s funny how we call this ‘lifecycle management’ like it’s a business seminar and not a decades-long heist. The 12% statistic? That’s the real kicker. It means 88% of these patents are just... noise. Legal static. We’re drowning in paperwork while people die waiting for a $5 pill. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way.

Renee Stringer

February 3, 2026 AT 04:03It's appalling that we allow this. If a company can extend a monopoly by changing the color of a pill, then the entire patent system is a farce. And yet, we praise these companies as ‘innovators’. We are being gaslit by corporate PR. There is no moral high ground here. Only profit.