When you pick up a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or amoxicillin, you might not think about who made it - but that decision is what keeps your copay low. The reason your generic pills cost a fraction of the brand-name version isn’t because of charity or goodwill. It’s because multiple generic manufacturers are fighting over your business. And that competition? It’s the single biggest reason drug prices have stayed affordable for millions.

Think about it: if only one company made a generic version of a drug, they could charge whatever they wanted. But when five, ten, or even twenty companies all make the same pill, they can’t just raise prices. They have to undercut each other. That’s basic economics - and it’s working exactly as it should.

How Competition Slashes Drug Prices

The numbers don’t lie. A 2021 study published in JAMA Network Open looked at 50 brand-name drugs and tracked what happened when generics entered the market. The results were clear:

- One generic competitor? Price dropped 17%.

- Two competitors? Down 39.5%.

- Three competitors? 52.5% lower.

- Four or more? A 70.2% drop - nearly three-quarters off the original price.

That’s not a coincidence. The more companies making the same drug, the harder they have to work to win your pharmacy’s business. And pharmacies? They’ll switch to the cheapest option every time.

The FDA estimates that generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion between 2010 and 2019. In 2022 alone, 742 new generic approvals were projected to save $14.5 billion annually. That’s not just savings - that’s money staying in people’s pockets instead of going to pharmaceutical executives.

Why Some Generics Still Cost Too Much

But here’s the problem: not every generic drug has multiple makers. In fact, nearly half of all generic drugs on the market have only one or two manufacturers. And when that happens, prices don’t drop - they spike.

Take a drug like levetiracetam, used to treat seizures. A few years ago, five companies made it. Prices were stable, under $20 for a 30-day supply. Then two of the manufacturers quit. The remaining three raised prices. Within months, the same prescription jumped to over $150. Patients had to switch medications, some with serious side effects.

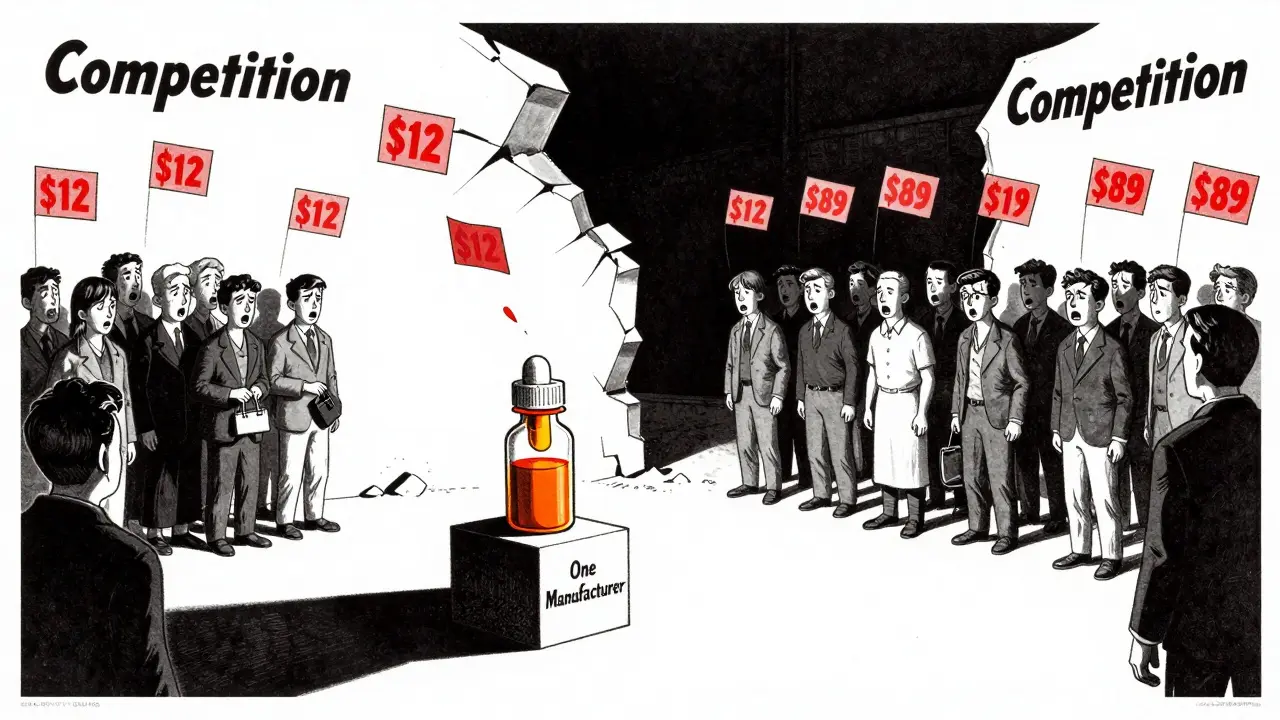

Reddit threads and patient forums are full of stories like this. One user in r/pharmacy described a $400 price hike on a generic antibiotic after just one manufacturer left the market. Another reported their blood pressure med went from $12 to $89 in six months - no change in dosage, no change in pill, just fewer companies making it.

Why do manufacturers leave? Because margins are thin. The average generic drug maker earns less than $800,000 a year per product. When you’re selling a pill for pennies, you can’t afford to lose money on recalls, supply chain delays, or FDA inspections. So when things get tough, they walk away.

Oral Pills vs. Injectables: The Competition Divide

Not all drugs are created equal. The most competitive market is for simple, oral pills - things like statins, antibiotics, or diabetes meds. These are easy to make. The chemistry is well understood. The equipment is cheap. That’s why you’ll find eight or nine companies making metformin.

But injectable or infused drugs? Those are different. They’re harder to produce. The manufacturing process is complex. The FDA approval process takes longer. And fewer companies have the capability. That’s why you rarely see more than two manufacturers for insulin, epinephrine auto-injectors, or IV antibiotics. And because competition is limited, prices stay high.

The same goes for biologics - complex drugs made from living cells. Even when biosimilars (the generic version of biologics) enter the market, they rarely drive prices down like traditional generics. A 2021 study found that if biosimilars were treated like regular generics under Medicare, spending on biologics could have dropped nearly 27% over five years. But they’re not. So prices stay inflated.

The Consolidation Crisis

Over the last decade, the generic drug industry has been quietly shrinking. Between 2014 and 2016, nearly 100 small generic manufacturers were bought out by larger companies. Today, a handful of firms - like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz - control the majority of the market.

That’s not competition. That’s consolidation. And it’s dangerous. When one company owns 70% of the supply for a critical drug, they can quietly raise prices without fear of losing customers. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has flagged this as a major risk. In 2021, they challenged two mergers that would have cut competition for generic antibiotics and blood pressure meds.

But the problem is hidden. Most people don’t know which company makes their generic. The label just says “Actavis” or “Sandoz.” There’s no way for a patient to know if their pill is made by one of ten competitors - or just one.

What You Can Do

You can’t control who manufactures your drug. But you can control where you buy it - and how you ask for it.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare. These apps show real-time prices across pharmacies. Sometimes the same generic costs $3 at one store and $45 at another.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there another generic manufacturer available?” If your pharmacy only carries one brand, they can often order another.

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book. It lists all approved generics and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. Look for AB-rated drugs - those are interchangeable with the brand.

- Don’t assume all generics are the same. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin or levothyroxine - switching brands can cause issues. Talk to your doctor before swapping.

And if your drug suddenly becomes unaffordable? That’s a red flag. It likely means competition has collapsed. Contact your prescriber. Ask about alternatives. There’s almost always another option with more manufacturers.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper. They’re essential. They make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition.

Without multiple manufacturers, the system collapses. We’d be paying brand-name prices for every pill. Medicare and Medicaid budgets would explode. Millions of people would skip doses because they can’t afford them.

The FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan and the CREATES Act were designed to keep new generic makers in the game. But they’re fighting against consolidation, supply chain chaos, and shrinking profit margins.

The truth is simple: more manufacturers = lower prices. Fewer manufacturers = higher prices, shortages, and risk. We need more companies making generics - not fewer. And we need to demand transparency so we know who’s making our medicine.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

It’s all about competition. If five companies make the same generic drug, they’ll fight to offer the lowest price - often under $10 for a 30-day supply. But if only one company makes it, they can charge $50 or more. Price differences aren’t about quality - they’re about how many makers are in the market.

Can I ask my pharmacist to switch to a different generic brand?

Yes, absolutely. Pharmacists can substitute generics with the same therapeutic rating (AB-rated) unless your doctor says “do not substitute.” If your current generic is too expensive, ask if another manufacturer’s version is available. Many pharmacies will order it for you at a lower price.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also meet the same strict standards for purity and performance. The only differences are inactive ingredients - like fillers or dyes - which don’t affect how the drug works.

Why aren’t there more generic manufacturers?

Making generics is risky and low-margin. FDA inspections are strict, and production costs are high. Many small companies can’t survive if one batch fails or if prices drop too fast. Plus, mergers have reduced the number of independent makers. Fewer companies mean less competition - and higher prices.

What’s being done to fix the lack of competition?

The FDA launched its Drug Competition Action Plan in 2017 to speed up approvals and block anti-competitive tactics. The CREATES Act of 2019 prevents brand companies from blocking generic makers from accessing samples needed for testing. The FTC has also started challenging mergers that reduce competition. But progress is slow, and more oversight is needed.

John Cena

February 18, 2026 AT 18:58Had a friend on insulin last year. Price jumped from $35 to $280 in six months. No change in the pill, just fewer makers. We found a different generic through GoodRx for $12. Crazy how much it matters who makes it. I never thought about this until it hit home.

Maddi Barnes

February 19, 2026 AT 09:05OMG I just realized I’ve been paying $89 for my blood pressure med because my pharmacy only stocks one brand 😭

Turns out there are FOUR other AB-rated generics available and the cheapest one is $4. I feel so dumb. Why does no one talk about this? The system is rigged to keep us clueless. Also, I just checked the FDA Orange Book and now I’m obsessed. I’ve been researching my meds like it’s a Netflix doc. #GenericWhisperer

Jonathan Rutter

February 19, 2026 AT 15:30You people are missing the real issue. It’s not about competition - it’s about greed. These ‘generic’ companies are still part of big pharma empires. Teva? Sandoz? They’re subsidiaries of the same oligarchs who run the brand-name game. The whole ‘multiple manufacturers’ thing is a distraction. They let a few players in so you think the market’s fair - but they control the supply chain, the FDA approval pipeline, and the pharmacy contracts. It’s all choreographed. You’re not saving money - you’re just getting a slightly better seat on the same sinking ship.

Jana Eiffel

February 20, 2026 AT 09:24It is of paramount importance to recognize that the structural integrity of pharmaceutical competition is predicated upon regulatory transparency and market accessibility. The current paradigm, wherein consolidation among multinational generics manufacturers has resulted in de facto monopolistic control over essential therapeutics, constitutes a systemic failure of antitrust enforcement. The FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan, while commendable in intent, lacks sufficient teeth to counteract the strategic barriers erected by incumbent firms. A recalibration of procurement policy at the federal level - particularly within Medicare and Medicaid - is not merely advisable but ethically imperative.

Jayanta Boruah

February 20, 2026 AT 10:14In India, we have over 20 manufacturers for metformin. Price: $0.50 for 30 tablets. US system is broken. Why? Because you let corporations write the rules. Simple.

Taylor Mead

February 21, 2026 AT 22:37Just switched my generic lisinopril from the $45 brand to the $7 one using GoodRx. No difference in how I feel. I used to think generics were ‘weaker’ - turns out I was just being scammed by my pharmacy. If you’re paying more than $10 for a common generic, you’re doing it wrong. Seriously, check your options. It’s not rocket science.

Benjamin Fox

February 23, 2026 AT 03:55AMERICA NEEDS MORE GENERIC MAKERS NOT LESS 🇺🇸

STOP LETTING BIG PHARMA STRANGLE THE MARKET

MY DAD DIED BECAUSE HE COULDN’T AFFORD HIS MEDS

THIS ISN’T A DRUG ISSUE - IT’S A MORAL ISSUE

Freddy King

February 23, 2026 AT 08:16Look - the whole ‘competition drives prices down’ narrative is a neoliberal fantasy. You’re assuming rational actors and free markets, but the generic pharma space is a prisoner’s dilemma with regulatory capture. Margins are so thin because the system is designed to incentivize exit, not entry. The FDA’s approval process is a bottleneck, and the CREATES Act? Too little, too late. We need public manufacturing - not more private players. The market didn’t fail. It was engineered to fail.

Laura B

February 25, 2026 AT 05:58I work in a pharmacy and I see this every day. Patients come in confused, angry, scared because their $12 pill became $80. We have to manually check the Orange Book, call distributors, and sometimes order from scratch. It’s not the patient’s fault - it’s the system. I wish we could just show them a simple chart: ‘This pill has 8 makers → $5. This one has 1 → $75.’ But we can’t. The tech doesn’t exist. We’re stuck in the dark ages.

Robin bremer

February 25, 2026 AT 23:36so i just found out my generic adderall is made by a company that got bought by teva??

and now it’s 3x more expensive??

wait so i’ve been paying extra for the same pill??

im so mad rn lmao