When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most common and trusted method used worldwide to prove that a generic drug behaves identically to the original in your body.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

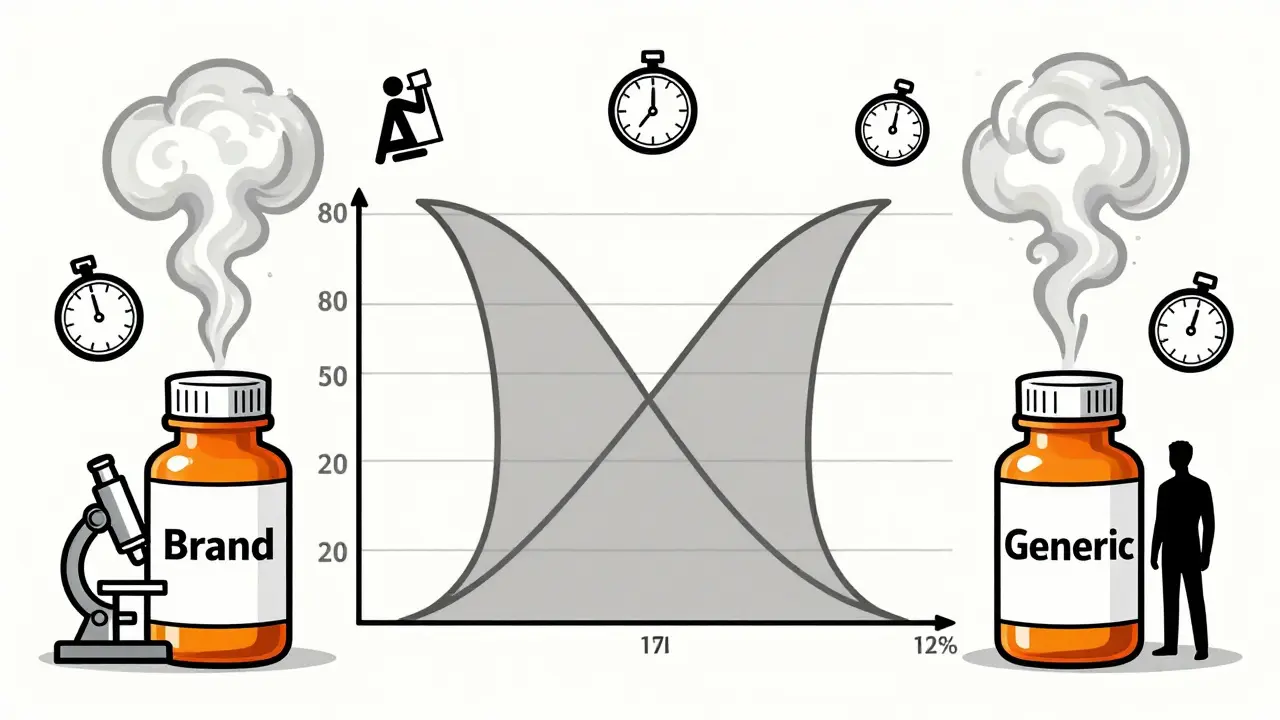

Pharmacokinetic studies track how a drug moves through your body: how fast it’s absorbed, how high it goes in your bloodstream, and how long it stays there. The two key numbers they measure are Cmax (the highest concentration reached) and AUC (the total exposure over time). These aren’t just lab numbers-they directly reflect whether your body will get the same dose of medicine, at the same speed, as the brand-name drug. For most oral drugs, regulators require that the 90% confidence interval for these values falls between 80% and 125% when comparing the generic to the original. That means if the brand-name drug hits a Cmax of 100 ng/mL, the generic can range from 80 to 125 ng/mL and still be considered equivalent. It’s not about being identical-it’s about being close enough that your health won’t be affected. These studies are done in healthy volunteers, usually between 24 and 36 people, using a crossover design. That means each person takes both the brand and the generic at different times, with a washout period in between. This cuts out individual differences in metabolism and gives a clean comparison.Why This Isn’t Always the Full Story

Many people think pharmacokinetic studies are the ultimate proof-like a gold standard. But that’s misleading. The FDA itself says bioequivalence isn’t a gold standard. It’s a scientifically sound surrogate. It works brilliantly for most pills you swallow, but it breaks down for other types of drugs. Take topical creams, inhalers, or injectables. You can’t easily measure drug levels in the blood for these. A skin cream might work perfectly on the surface, but blood tests show nothing. That’s why for topical products, researchers are turning to dermatopharmacokinetic methods-measuring drug levels directly in the skin using tiny suction devices-or in vitro permeation tests using human skin samples. One study found these methods were more accurate and less variable than trying to run clinical trials with hundreds of patients. Even more telling: there are documented cases where two generics, both passing pharmacokinetic tests and matching the brand name in every chemical way, still caused different effects in patients. One PLOS ONE study in 2010 found that two generic versions of gentamicin, made by reputable companies and passing all standard tests, had wildly different clinical outcomes. The active ingredient was identical. The dissolution profile was perfect. But the body responded differently. Why? Because small differences in excipients-fillers, binders, coatings-can change how the drug releases or is absorbed, even if the main ingredient is the same.Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs: When the Margin Is Tiny

For drugs like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin, the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. A 10% change in absorption might mean a blood clot or a seizure. That’s why regulators apply tighter rules for these drugs. The FDA now requires a 90-111% equivalence range for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, not the usual 80-125%. Some countries, like Germany and Canada, have even stricter standards. In Australia, pharmacists are required to notify prescribers if a patient switches between NTI generics, because even small variations can matter. This is where the real challenge lies. A generic manufacturer might spend $800,000 and 18 months running bioequivalence studies, only to find that their formulation still falls outside the tighter limits. That’s why many companies invest early in biopharmaceutics classification system (BCS) studies. If a drug is BCS Class I-highly soluble and highly permeable-it might qualify for a waiver, skipping human trials entirely. But that only applies to about 15% of all drugs.

The Cost and Complexity Behind Every Generic Pill

Behind every generic drug you buy is a multi-million-dollar scientific effort. A single bioequivalence study can cost between $300,000 and $1 million. Add in formulation development, regulatory submissions, and compliance, and the total investment can hit $2-3 million per product. And it’s not just about money. The timeline is long. From the moment a company starts formulating a generic version, it can take 12 to 18 months just to get to the clinical trial phase. Then there’s the regulatory review. The FDA alone has over 1,857 product-specific guidance documents for bioequivalence-each one tailored to a specific drug’s quirks. A drug for epilepsy has different requirements than one for high blood pressure. A modified-release tablet has different rules than a quick-dissolve tablet. That’s why many generic companies now work closely with regulators early in development. Instead of guessing what’s needed, they ask: “What do you need to approve this?” This saves time, money, and avoids costly rework.What’s Changing in Bioequivalence Testing

The field is evolving. Traditional pharmacokinetic studies aren’t going away-but they’re no longer the only tool. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is gaining traction. Using computer simulations based on human anatomy, drug properties, and absorption data, scientists can now predict how a drug will behave without running a human study. The FDA started accepting PBPK models for bioequivalence waivers in 2020-for certain BCS Class I drugs. This could cut development time by months and reduce the need for human volunteers. In vitro testing is also improving. Dissolution testing, once just a quality check, is now being used to predict in vivo performance. If two formulations dissolve at nearly identical rates under multiple conditions (pH, agitation, temperature), regulators are more willing to accept that as proof of equivalence-especially when combined with modeling. Even the WHO and EMA are moving toward more flexible approaches. The European Medicines Agency, historically more rigid than the FDA, now accepts product-specific guidance for complex drugs. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has published M13A, a global standard for immediate-release products, adopted by 35 countries as of 2023.

Is the System Working?

The numbers say yes. In 2022, the FDA approved 95% of generic applications using pharmacokinetic bioequivalence studies. The global generic market hit $467 billion that year. Millions of patients rely on these cheaper alternatives every day. But success doesn’t mean perfection. There are still cases where patients report differences after switching generics-especially with NTI drugs. These aren’t always due to the drug itself. Sometimes, it’s the patient’s expectation. Sometimes, it’s a change in fillers that affects stomach sensitivity. But when a patient’s condition worsens after a switch, regulators take notice. That’s why transparency matters. Some countries now require pharmacists to log which generic version was dispensed. Others track adverse events linked to specific manufacturers. It’s not about distrust-it’s about accountability.What This Means for You

If you take a generic drug, you can be confident it’s been tested rigorously. The system works for most people, most of the time. But if you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or thyroid hormone-pay attention. If you switch brands and notice changes in how you feel, tell your doctor. Don’t assume it’s “all in your head.” For the rest of us, the system is quietly working behind the scenes. It’s not glamorous. It’s not perfect. But it’s the reason you can get a month’s supply of blood pressure medication for $5 instead of $300.Are pharmacokinetic studies the only way to prove generic drugs are equivalent?

No. While pharmacokinetic studies are the most common method, especially for oral drugs, other approaches exist. For topical creams, in vitro permeation tests or dermatopharmacokinetic methods are used. For some drugs, clinical endpoint studies (measuring actual patient outcomes) are required, though they’re expensive and rare. In vitro dissolution testing and computer modeling (PBPK) are also accepted in specific cases, especially for highly soluble drugs.

Why do some people say generic drugs don’t work as well?

Most of the time, it’s not the drug itself. The active ingredient is the same. But differences in inactive ingredients-like fillers, coatings, or binders-can affect how quickly the drug dissolves or how your stomach reacts. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for those on narrow therapeutic index drugs (like warfarin or thyroid meds), even small changes can cause noticeable effects. If you feel different after switching generics, talk to your doctor. It’s not always psychological.

Do all countries use the same bioequivalence standards?

No. The FDA and EMA have different approaches. The FDA uses product-specific guidelines, meaning each drug has its own rules. The EMA has traditionally used a one-size-fits-all approach, though it’s moving toward more flexibility. Some countries, like Australia and Canada, have tighter limits for narrow therapeutic index drugs. The WHO promotes harmonization, but implementation varies widely, especially in emerging markets.

Can a generic drug pass bioequivalence tests but still be unsafe?

Yes, but it’s rare. Bioequivalence studies focus on absorption, not long-term effects. A drug might have identical Cmax and AUC but contain a different impurity or excipient that causes an allergic reaction or interacts with other meds. That’s why post-market surveillance is critical. Regulatory agencies monitor adverse events after approval. If a pattern emerges, they can pull the product or require new testing.

How long do pharmacokinetic studies take, and how much do they cost?

A typical bioequivalence study takes 12 to 18 months from start to finish, including formulation development, regulatory approval, and clinical testing. The cost ranges from $300,000 to $1 million USD per study, depending on complexity. For modified-release or complex formulations, costs can exceed $2 million. That’s why many generic companies focus on simpler drugs first.

John Rose

January 28, 2026 AT 00:07It's wild how much science goes into something most people just grab off the shelf. I never realized how much variation is allowed between generics and brand names-80% to 125%? That’s a huge range. But I guess if it works for millions, it works.

Still, I’m glad they’re starting to use PBPK modeling. It’s about time we moved beyond just sticking needles in healthy volunteers.

Also, the part about excipients changing absorption? That’s the quiet killer. Nobody talks about it, but it’s real.

Good post. Really breaks down the myth that ‘generic = cheap = bad’.

Colin Pierce

January 29, 2026 AT 11:38As someone who works in clinical pharmacy, I see this every day. Patients get switched from one generic to another and swear something’s off-usually it’s the filler. Corn starch vs. lactose can mess with gut motility. Not the drug, just the delivery.

For NTI drugs? Always check the manufacturer. Some generics are just better formulated. Not because they’re ‘better’-just more consistent.

And yeah, PBPK is the future. We’re already using it for a few drugs in our hospital. Saves time, money, and avoids unnecessary testing.

Amber Daugs

January 30, 2026 AT 05:53Of course the FDA says it’s not a ‘gold standard’-they’re just covering their butts. If they admitted the system is flawed, people would panic. But let’s be real: if you’re on warfarin and your INR spikes after switching generics, you’re not imagining it.

And don’t get me started on how some foreign manufacturers cut corners. You think your $5 generic is made in the US? Laughable. It’s probably from a factory in India with no real oversight.

Don’t believe the hype. The system is broken, and we’re all just hoping we don’t get the bad batch.

Jeffrey Carroll

January 31, 2026 AT 15:02The fact that regulators accept dissolution testing as a proxy for bioequivalence is fascinating. It’s like saying ‘if it dissolves the same way in a beaker, it’ll behave the same in your gut.’

It’s elegant, really. Reduces human testing, speeds up approval, and still maintains safety margins.

But I wonder how many of these models are validated across diverse populations? Most data comes from young, healthy, Caucasian volunteers. What about elderly patients or those with GI disorders?

Still, impressive how far we’ve come.

Mindee Coulter

February 2, 2026 AT 00:51I switched from brand to generic for my thyroid med and felt like a zombie for two weeks. Told my doctor. They said it was psychosomatic. I didn’t believe them. Switched back. Back to normal. Now I always ask for the same generic. No more guessing.

Bryan Fracchia

February 2, 2026 AT 20:02It’s funny how we treat medicine like it’s some kind of magic potion. We assume the pill is the whole story. But it’s not. It’s the pill, the coating, the filler, your stomach acid, your gut bacteria, your liver enzymes, your mood, your sleep, your stress levels…

Pharmacokinetics gives us a snapshot. A very useful one. But it’s still just a snapshot.

Maybe the real question isn’t ‘are generics equivalent?’ but ‘how do we make the system more responsive to individual variation?’

Because if your body doesn’t respond the same way, the science doesn’t care. You’re just a data point.

Lance Long

February 3, 2026 AT 02:30Let me tell you something. I’ve been on the same generic for 8 years. Same bottle. Same pharmacy. Same manufacturer.

Then one day, I opened a new bottle. Felt like someone slipped me a sedative. My hands shook. My brain fogged. I thought I was having a stroke.

Turns out-same active ingredient. Different binder. Same company. Different batch.

I called the pharmacy. They said, ‘It’s still the same drug.’

No. It’s not. It’s the same molecule. But the medicine? Not even close.

Doctors need to start listening. Patients aren’t crazy. We’re just the ones who notice the difference.

And yeah, I’m still on it. Because I can’t afford the brand. But I’m not blind to what’s happening.

fiona vaz

February 3, 2026 AT 10:55I work in a rural clinic. We prescribe generics because that’s what patients can afford. But I’ve learned to track which brand each patient responds to. Some do better with one manufacturer’s version of levothyroxine. Others with another.

It’s not ideal, but it’s practical. We don’t have the luxury of ‘gold standards.’ We have patients who need meds today.

So we document. We listen. We adjust.

It’s messy. But it works.

And honestly? That’s what healthcare should be-adaptive, not theoretical.

Sue Latham

February 3, 2026 AT 22:15Oh honey. You really think this is all scientific? Please. The FDA approves generics based on paperwork. Real testing? That’s for the rich. Most generics are made in places where the inspectors get paid off.

And don’t get me started on how the big pharma companies own the patent expiration timeline. They delay generics for years, then sell their own version as ‘authorized generics’ at the same price.

This whole system is rigged. You’re not saving money-you’re paying for a gamble.

And if you’re lucky? You’ll get the version that doesn’t make you vomit.

Lexi Karuzis

February 5, 2026 AT 06:30!!! THE FDA IS LYING TO YOU !!! THEY KNOW THAT GENERICS CAN BE TOXIC BUT THEY LET THEM THROUGH BECAUSE THEY'RE PAID OFF BY BIG PHARMA !!! I READ A BLOG POST THAT SAID THE SAME EXCIPIENT IN TWO GENERICS CAUSED A PATIENT TO HAVE A SEIZURE AND THE FDA COVERED IT UP !!! THEY'RE HIDING THE TRUTH FROM US !!! YOU THINK YOUR WARBIN IS SAFE? THINK AGAIN !!! THEY'RE TESTING ON YOU !!!

Mark Alan

February 7, 2026 AT 02:43USA 🇺🇸 BEST PHARMACEUTICALS IN THE WORLD 🇺🇸

EUROPE? THEY LET ANYTHING THROUGH. 🇪🇺

INDIA? 🤮

CHINA? 🤢

WE GOT THE BEST STANDARDS. YOU THINK WE’RE JUST GIVING OUT FREE MEDS? NOPE. WE’RE THE ONLY ONES WHO CARE ABOUT YOUR LIFE. 🇺🇸

EVERY OTHER COUNTRY IS A MEDICAL DUMPSTER FIRE. 🚒💊

James Dwyer

February 8, 2026 AT 14:59It’s not about the drug. It’s about the system. We treat medicine like a commodity. But it’s not. It’s biology.

And biology doesn’t care about cost-cutting or regulatory loopholes.

So yeah, the system works-for most people, most of the time.

But when it fails? It fails hard.

And we act like it’s fine because the numbers look good.

That’s not progress. That’s negligence dressed up as efficiency.

jonathan soba

February 10, 2026 AT 14:39The 80-125% range is statistically convenient, not biologically meaningful. It’s a compromise between scientific rigor and commercial feasibility.

And yet, we treat it as gospel.

Meanwhile, in the UK, we’ve had multiple recalls of generic antiepileptics due to inconsistent dissolution profiles-despite passing bioequivalence. The system is not robust. It’s brittle.

And now we’re replacing human trials with computer models? That’s not innovation. That’s outsourcing risk to algorithms that don’t understand human variability.

It’s a house of cards. And someone’s going to get hurt before it collapses.

Chris Urdilas

February 10, 2026 AT 20:45So let me get this straight. We spend $2 million to prove a generic is ‘close enough’ to a brand name…

…and then we switch patients between different generics every few months because insurance changes their preferred brand?

That’s not science. That’s financial roulette.

And we wonder why people hate the healthcare system.

Also, PBPK models? Cool. But if the input data is garbage, the output is garbage too.

So… who’s validating the models?

And who’s paying for it?

…probably the same people who made the original drug.

Oh, I see. It’s all connected.

Phil Davis

February 12, 2026 AT 09:00People complain about generics. But let’s be honest: if you’re on warfarin, you’re probably already paranoid about your INR. If you switch generics and feel weird, you’re going to blame the drug.

But what if it’s just your body adjusting? Or stress? Or sleep? Or coffee intake?

It’s not that the system is broken. It’s that we’ve turned medicine into a personal identity. ‘This pill makes me feel like me.’

But pills don’t make you. Your body does.

And sometimes, it just needs time to adapt.

Still. If it doesn’t work? Change it. Don’t assume the system’s broken. Just change the pill.

John Rose

February 13, 2026 AT 11:40Interesting point about the body adapting. I had the same thing with my blood pressure med. Switched generics, felt dizzy for a week. Thought it was the drug. Turned out, I’d also started drinking more coffee. The combo was the issue.

But here’s the thing-doctors rarely ask about lifestyle changes when patients report side effects.

They just assume the generic is ‘bad.’

Maybe we need better communication, not better regulations.