Handling chemotherapy isn’t like handling any other medication. These drugs are designed to kill fast-growing cells - and while they target cancer, they don’t know the difference between a tumor and healthy tissue. That’s why chemotherapy safety isn’t optional. It’s a non-negotiable part of every step, from the pharmacy to the patient’s bedside - and even at home.

Why Chemotherapy Is Different

Chemotherapy drugs are classified as hazardous. They can cause skin rashes, reproductive harm, organ damage, and even cancer in people exposed over time. Nurses, pharmacists, caregivers, and even family members can be at risk if proper protocols aren’t followed. This isn’t theoretical. Studies dating back to the 1990s show that traces of these drugs are found on gloves, countertops, and even in the air after administration. One 2015 study found that outer gloves used during chemo prep were contaminated in 100% of cases - and that contamination transferred to skin and surfaces. The 2024 update from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) moved beyond calling these drugs "chemotherapy." They now use the term antineoplastic therapy because modern cancer treatments include targeted drugs, immunotherapies, and antibody-drug conjugates - all of which carry similar risks. Whether it’s paclitaxel, doxorubicin, or a new bispecific antibody, the safety rules apply.Protecting the Team: The Right Gear

Personal protective equipment (PPE) isn’t just a suggestion. It’s mandatory. The current standard requires:- Two pairs of chemotherapy-tested gloves - not just any nitrile. These gloves are tested to resist permeation by hazardous drugs. Single gloves or non-certified ones won’t cut it.

- Impermeable gowns with closed backs and long sleeves. Cotton gowns? Not enough. They absorb spills.

- Eye protection - goggles or face shields - whenever there’s any chance of splashing.

- Respirators (N95 or higher) if aerosols are possible, like during IV bag changes or spill cleanup.

Preparing and Dispensing: The Four-Step Verification

The biggest change in the 2024 standards? The fourth verification step. Before, most facilities used two or three checks. Now, there’s a mandatory fourth - done right at the patient’s bedside. Here’s how it works:- Pharmacist checks the order against the patient’s chart.

- A second pharmacist or nurse verifies the drug, dose, route, and patient ID.

- A third person - often a nurse preparing the infusion - double-checks everything again.

- At the bedside, two licensed clinicians confirm the patient’s name and date of birth using two identifiers (like name + birthdate), then confirm the drug name and dose out loud - in front of the patient.

Administering Safely: More Than Just an IV

The way you give the drug matters just as much as the dose. For IV infusions:- Use closed-system transfer devices (CSTDs) to prevent vapor escape when drawing up or connecting bags. These devices are now standard in most hospitals - but still missing in 43% of rural clinics.

- Never use regular IV tubing. Use filtered tubing designed for cytotoxic drugs.

- For oral chemo, always dispense in child-resistant containers. Never leave pills on the counter.

- For drugs like carmustine or thiotepa - which penetrate gloves faster - double gloving isn’t optional. It’s required.

What Happens After? Monitoring for CRS and More

Newer therapies like CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies can trigger cytokine release syndrome (CRS) - a dangerous immune overreaction. Symptoms include high fever, low blood pressure, trouble breathing, and organ failure. The 2024 standards now require every facility to have a CRS response plan ready. That means:- Tocilizumab (Actemra) and corticosteroids must be immediately accessible.

- Nurses must be trained to recognize early signs - even before the patient feels sick.

- Monitoring protocols must include vital signs every 15 minutes for the first hour, then hourly for at least 4 hours after infusion.

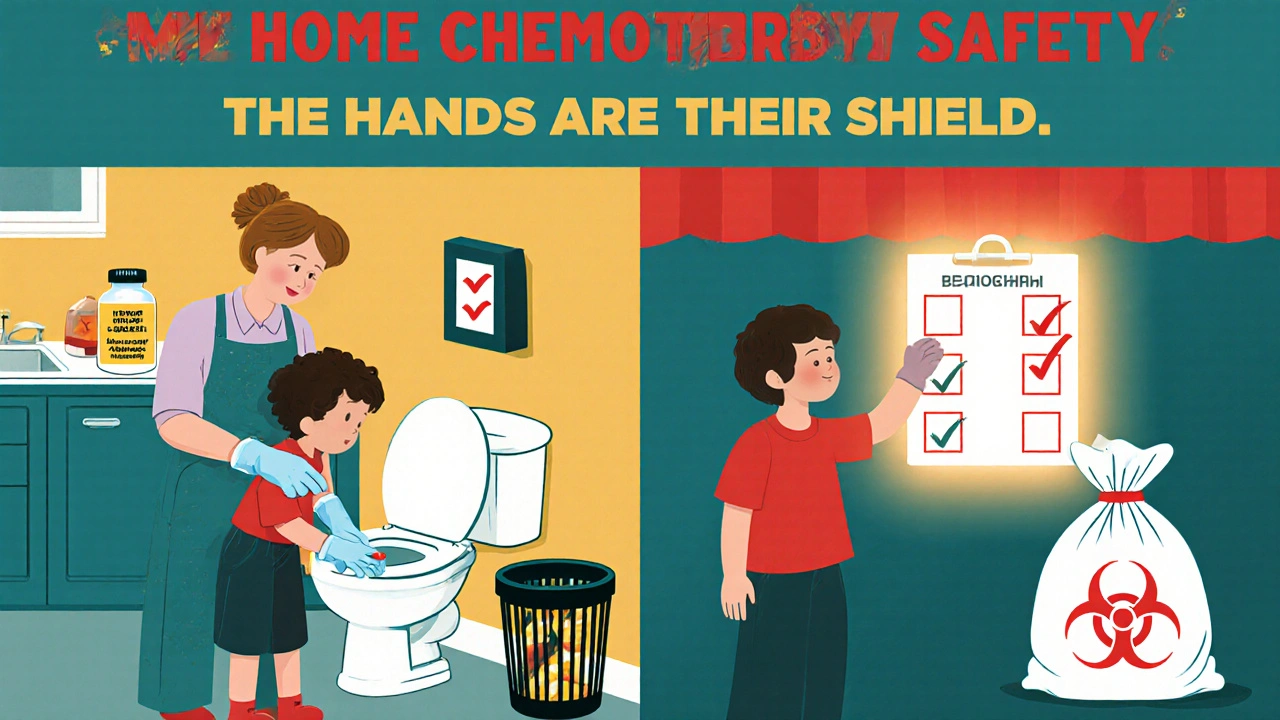

Home Chemotherapy: A Hidden Risk

More than 30% of cancer patients now get chemo at home. But safety protocols? They’re often incomplete. Caregivers are told to wear gloves when handling bodily fluids for 48-72 hours after treatment. They’re told to flush toilets twice. To use special disposal bags for syringes and pills. To keep meds out of reach of kids and pets. But here’s the problem: 65% of home caregivers say they feel unprepared. In 22% of home incidents, hazardous waste was thrown in regular trash. In 17%, spills were cleaned with paper towels - not the specialized chemo kits hospitals provide. The Cancer Support Community found that facilities using the ASCO-developed "Chemotherapy Safety at Home" toolkit saw a 41% drop in caregiver safety concerns. That toolkit includes visual guides, checklists, and video demos - things most patients never get.

Costs, Barriers, and Inequality

Implementing full safety standards isn’t cheap. A medium-sized clinic needs $22,000-$35,000 for facility upgrades, $8,500-$12,000 for staff training, and $4,200-$6,800 annually for PPE and waste disposal. Electronic health record systems often need custom builds - costing $15,000-$40,000 - just to support the four-step verification process. That’s why 43% of rural clinics can’t afford closed-system transfer devices. That’s why nurses in underserved areas are forced to cut corners. Dr. Sarah Temkin calls it a "two-tiered safety system" - where access to protection depends on your zip code. OSHA issued 142 citations for hazardous drug violations in 2022 - up 37% from 2021. Fines averaged $14,250 per violation. But many clinics still don’t report exposures. Only 41% of nurses who were exposed actually filed a report - fearing job loss or being labeled "difficult."What’s Next?

By January 2025, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) will require proof of fourth verification and CRS protocols for facility accreditation. Pilots for AI-assisted verification systems are launching at 12 top cancer centers - using image recognition to confirm patient IDs and drug labels before administration. A national certification for chemo handlers is expected by 2026. Until then, every facility must train staff for 8-12 hours initially, then 4 hours every year. Competency isn’t just a test - it’s a live demonstration. You have to show you can glove up, prep a bag, use a CSTD, and clean a spill - all without contamination.Final Thought: Safety Is a Habit

Chemotherapy safety isn’t about fear. It’s about discipline. It’s about doing the same thing, the same way, every time - even when you’re tired, busy, or overworked. It’s about asking, "Are we sure?" - not once, but four times. The data is clear: when protocols are followed, errors drop by 63%. Exposures drop by 78%. Nurses report higher confidence. Patients feel safer. And lives - both patients’ and providers’ - are protected. It’s not perfect. It’s not easy. But it’s necessary.Can chemotherapy drugs harm caregivers at home?

Yes. Chemotherapy drugs can remain active in bodily fluids like urine, vomit, and sweat for up to 72 hours after treatment. Without proper precautions - like wearing gloves, flushing toilets twice, and using special disposal bags - caregivers can be exposed through skin contact or inhalation. Studies show 22% of home incidents involve improper waste disposal, and 17% involve unsafe spill cleanup.

Why is a fourth verification step required before giving chemo?

The fourth verification - done at the bedside by two licensed staff using two patient identifiers - was added because 18% of chemotherapy errors in 2022 were due to patient misidentification. This step ensures the right drug goes to the right person. Facilities using this step saw a 52% drop in near-miss errors, according to internal data from oncology units.

Do I need special gloves for handling chemotherapy?

Yes. Regular nitrile gloves are not enough. You need chemotherapy-tested gloves that have been proven to resist permeation by hazardous drugs. These are tested under standards set by NIOSH and USP <800>. Double gloving is required for high-risk drugs like carmustine and thiotepa. Gloves must be changed immediately if torn or contaminated.

What is a closed-system transfer device (CSTD), and why is it important?

A CSTD is a device that prevents hazardous drugs from escaping into the air during preparation or administration. It creates a physical barrier between the drug container and the environment. CSTDs reduce airborne contamination by up to 90% and are now required by most hospital standards. They’re especially critical for volatile drugs and during IV bag changes.

What should I do if a chemotherapy spill happens?

Never use paper towels or regular cleaning supplies. Use a dedicated chemotherapy spill kit, which includes impermeable gloves, absorbent pads, and a biohazard bag. Contain the spill, put on PPE, then carefully absorb and dispose of the material. All contaminated items must be labeled as hazardous waste. Facilities are required to have spill kits readily available - and staff must be trained in their use.

Are there specific drugs that are more dangerous to handle?

Yes. NIOSH categorizes hazardous drugs into five risk groups. Drugs like carmustine, thiotepa, and mitomycin C are in the highest risk group because they penetrate gloves faster and are more toxic. These require double gloving, extra ventilation, and strict handling protocols. Even common drugs like cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide carry significant risk if not handled correctly.

How often do healthcare workers get exposed to chemotherapy drugs?

Exposures are more common than reported. While 78% of oncology nurses now work in facilities with formal exposure protocols, only 41% of exposed workers actually report incidents. Many fear blame, job consequences, or being seen as incompetent. Studies show contamination is found on hands, skin, and surfaces even when PPE is used - highlighting the need for strict procedures and culture change.

What is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and why is it part of chemotherapy safety?

CRS is a severe immune reaction triggered by some immunotherapies and CAR-T cell treatments. Symptoms include high fever, low blood pressure, and breathing trouble. Between 2018 and 2022, CRS cases increased 300%. If not treated immediately with drugs like tocilizumab, mortality rates reach 12-15%. The 2024 safety standards now require all facilities to have CRS antidotes on hand and staff trained to recognize early signs.

Michael Segbawu

November 29, 2025 AT 01:48This is why america needs to stop letting foreigners run our hospitals I seen a nurse in texas wear one glove and still handle chemo They dont even test the gloves right Its a joke

Aarti Ray

December 1, 2025 AT 01:05In india we dont have proper chemo rooms but still nurses do their best Sometimes they use old gloves just to save money But they care so much I saw my aunt get treated in a village clinic No CSTD no nothing But they held her hand and smiled Thats real medicine

Alexander Rolsen

December 2, 2025 AT 13:07This article is... overly emotional. The data is solid. The 18% misidentification rate is alarming. The 78% exposure reduction is undeniable. The cost figures are accurate. The OSHA citations are rising. The underreporting is systemic. The cultural incompetence in rural clinics is unacceptable. The lack of federal enforcement is criminal. The NCCN accreditation requirement is long overdue. The AI pilot programs are promising. The certification timeline is realistic. The only thing missing? Accountability.

Leah Doyle

December 3, 2025 AT 02:28I work in oncology and this made me cry 😭 I had a patient last week who asked me if her husband would get sick from her pills I didn't know what to say This guide would've helped me so much Thank you for writing this I'm printing it for our whole team

Michelle N Allen

December 3, 2025 AT 18:57I mean I get that chemo is dangerous but like... do we really need four people to check a name? I've seen nurses do it in under a minute and nothing bad ever happened. And the PPE? It's hot and uncomfortable and we're already overworked. I don't see why we need to spend thousands on fancy gloves when the patient is just gonna get the drug anyway. And home care? Most people don't even know how to use a toilet properly. Why are we treating them like they're in a lab?

Madison Malone

December 3, 2025 AT 19:41I just want to say thank you to all the nurses and pharmacists who do this every day I know it's scary I know it's exhausting But you're saving lives And if you're a caregiver at home You're doing something incredible too You don't need perfect gear You just need to care And that's enough

Graham Moyer-Stratton

December 5, 2025 AT 15:51Safety is a habit

tom charlton

December 7, 2025 AT 04:41The implementation of standardized protocols for antineoplastic therapy administration represents a critical advancement in occupational health and patient safety. The integration of closed-system transfer devices, mandatory four-step verification, and structured response protocols for cytokine release syndrome aligns with evidence-based best practices. It is imperative that institutions prioritize funding, training, and cultural accountability to ensure equitable access to these life-preserving measures across all geographic and socioeconomic contexts.

Jacob Hepworth-wain

December 8, 2025 AT 03:27I used to think the extra steps were just bureaucracy Then I saw a mistake happen It wasn't the drug It was the name We got lucky Now I double check everything Even when I'm tired Even when it's 3am Because someone's life is on the line

Craig Hartel

December 9, 2025 AT 18:14I love that this includes home care My sister got chemo at home for 6 months We had no idea what to do I wish someone had given us those video guides We used paper towels for a spill I feel so guilty now But I'm learning And I'm not alone This is the kind of info that saves families

anant ram

December 9, 2025 AT 23:14In India, we don't have CSTDs in most hospitals, but we use double gloves, and we clean everything with bleach... and we pray. The nurses here work 16-hour shifts and still follow every rule they can. The government doesn't fund this, but we do it anyway. We are not perfect, but we are not giving up.

Katrina Sofiya

December 10, 2025 AT 21:57The four-step verification protocol is not merely a procedural enhancement-it is a fundamental safeguard against human error in high-stakes clinical environments. The documented reduction in near-miss incidents by 52% in facilities implementing this standard is statistically and clinically significant. Furthermore, the requirement for live competency demonstrations ensures that procedural knowledge is not abstract, but embodied. This is not bureaucracy; it is bioethics in action.