Chronic heartburn isn’t just annoying-it’s a warning sign. If you’ve had acid reflux for more than five years, especially if it happens several times a week, you could be at risk for something more serious: Barrett’s esophagus. This isn’t just a worsened version of GERD. It’s a physical change in the lining of your esophagus that can quietly turn into cancer. And most people don’t know they have it until it’s too late.

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the normal tissue lining your esophagus-soft, pink, and made of squamous cells-gets replaced by a different kind of tissue: columnar cells that look like the lining of your intestines. This is called intestinal metaplasia. It’s your body’s attempt to protect itself from constant stomach acid. But this change comes with a cost.This condition was first described in 1950 by Norman Barrett, and today, about 5.6% of adults in the U.S. have it. Among people with long-term GERD, that number jumps to 10-15%. The risk isn’t evenly spread. Men are three times more likely to develop it than women. White men over 50 with a history of smoking, obesity, or chronic heartburn face the highest risk. It takes at least 10 years of frequent acid exposure for this change to occur.

The scary part? Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t cause new symptoms. You won’t suddenly feel different. You’ll still have heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, or trouble swallowing-but those are just your GERD symptoms continuing. That’s why so many people miss the diagnosis. The Esophageal Cancer Action Network found that 68% of patients had symptoms for over five years before being tested.

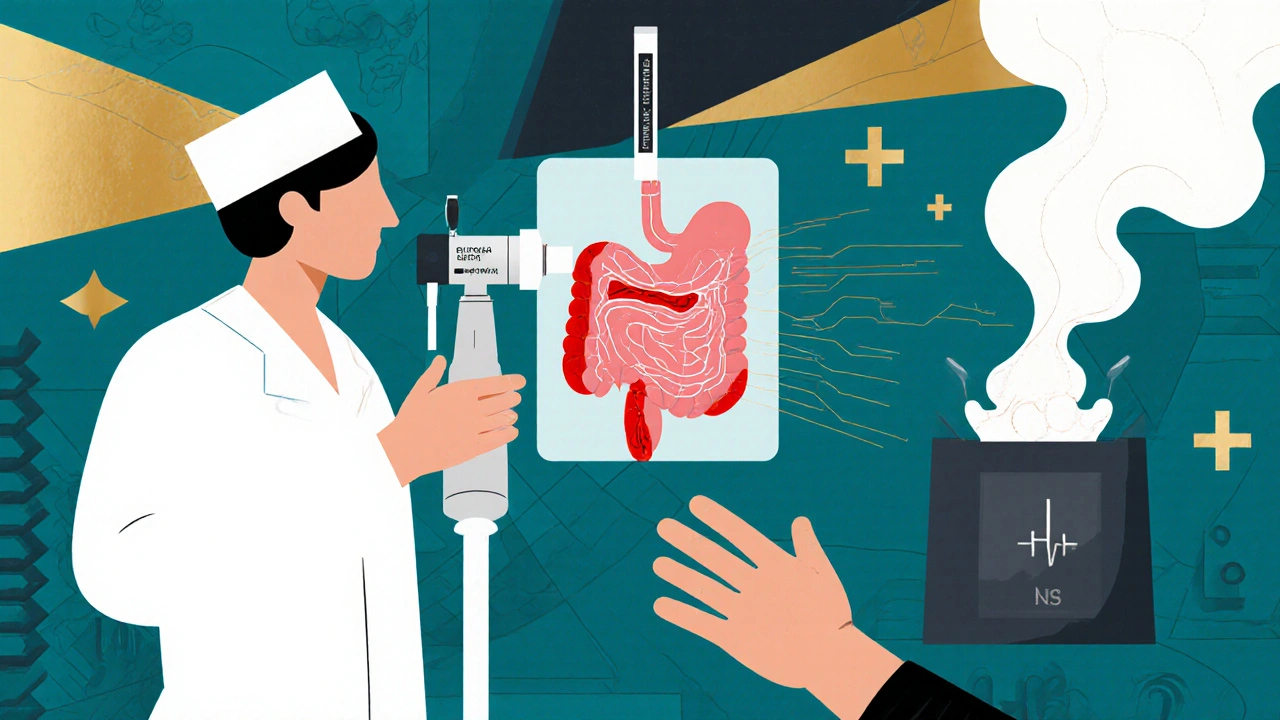

How Is It Diagnosed?

You can’t diagnose Barrett’s esophagus with a blood test or an X-ray. The only way is through an upper endoscopy. During this procedure, a thin, flexible tube with a camera goes down your throat. Doctors look for areas of salmon-colored tissue above the stomach junction-this is the visual clue.But seeing it isn’t enough. Biopsies are required. The standard is the Seattle protocol: taking four tissue samples every 1 to 2 centimeters along the abnormal area. That’s usually 12 to 24 biopsies total. Why so many? Because cancer doesn’t grow evenly. It can start in one tiny spot. Missing it is easy if you don’t sample enough.

Once biopsies are taken, pathologists classify the condition into stages:

- Non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE)-no precancerous changes yet

- Indefinite for dysplasia-unclear if changes are real or just inflammation

- Low-grade dysplasia (LGD)-early signs of abnormal cell growth

- High-grade dysplasia (HGD)-severe changes, almost cancer

High-grade dysplasia carries a 6-19% chance of turning into cancer each year. That’s why catching it early matters.

Who Should Be Screened?

Not everyone with heartburn needs an endoscopy. Screening is targeted. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends it for men who have:- Chronic GERD symptoms for more than 5 years

- Symptoms at least once a week

- At least one additional risk factor: age over 50, White race, smoking, obesity (BMI over 30), or a family history of esophageal cancer

Women and men without these extra risk factors are generally not screened. Why? Because the overall risk of cancer is low, and endoscopies are expensive and carry small risks. But if you’re a 55-year-old White man who’s had daily heartburn since your 30s and smokes? You’re in the high-risk group.

And here’s the problem: guidelines aren’t always followed. One Reddit user shared that three different gastroenterologists gave him three different surveillance schedules for his non-dysplastic Barrett’s. That inconsistency causes confusion and anxiety.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

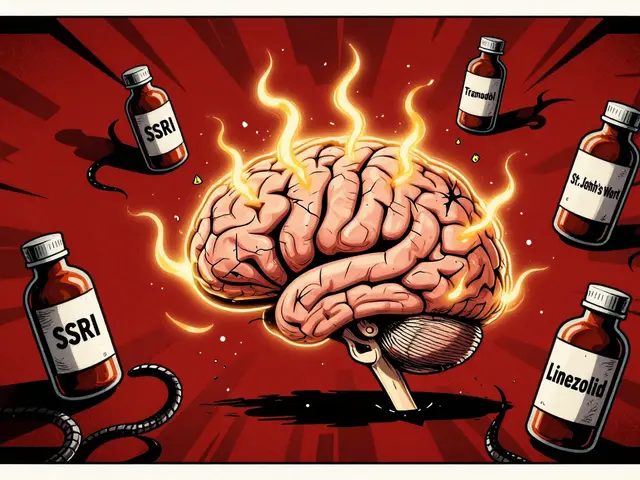

If you’re diagnosed with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, you’re not facing cancer tomorrow. But you’re not off the hook either. Surveillance is key. Most guidelines recommend a repeat endoscopy every 3 to 5 years.If you have low-grade dysplasia, things get more urgent. You’ll need a second opinion from a specialist pathologist-because diagnosing LGD is tricky. Then, surveillance every 6 to 12 months. In 2022, new guidelines expanded treatment options: radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is now recommended for all confirmed LGD cases. This procedure uses heat to destroy the abnormal tissue. Studies show 94% of patients stay free of dysplasia five years after treatment.

High-grade dysplasia? That’s a red flag. Most doctors skip surveillance and go straight to treatment. RFA works here too-with success rates of 90-98%. Some patients also get cryotherapy (freezing) or endoscopic mucosal resection (removing the damaged layer). After treatment, you still need regular checkups, but your cancer risk drops dramatically.

One Mayo Clinic patient had HGD and underwent RFA. Six months later, follow-up biopsies showed no trace of Barrett’s tissue. He’s now cancer-free and monitored yearly.

Can You Prevent Progression?

Medication alone won’t cut it. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole or pantoprazole reduce acid and help symptoms-but they don’t always stop the damage. Studies show only 55-70% of patients achieve full acid suppression, even on high doses. That’s why symptom relief doesn’t equal protection.You need lifestyle changes:

- Stop eating 3 hours before bed

- Elevate the head of your bed by 6-8 inches

- Avoid fatty foods, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, and spicy meals

- Lose weight if your BMI is over 25

- Quit smoking

These aren’t suggestions-they’re medical necessities. Obesity increases pressure on the stomach, pushing acid upward. Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter. Both make Barrett’s worse.

High-dose PPIs (like 40mg omeprazole twice daily) are often prescribed, but even then, some patients need pH monitoring to confirm acid suppression. If your symptoms improve but your esophagus is still being damaged, you’re not fully protected.

What’s New in Screening?

The biggest challenge isn’t treating Barrett’s-it’s finding who will progress to cancer. Only 5% of people with Barrett’s ever develop adenocarcinoma. That means 95% of people undergoing regular endoscopies are doing it for no reason. It’s costly, invasive, and stressful.New tools are emerging. The TissueCypher Barrett’s Esophagus Assay, approved by Medicare in 2021, analyzes tissue samples for molecular markers. In a 635-patient study, it had a 96% negative predictive value-meaning if the test says you’re low risk, you almost certainly won’t develop cancer in the next three years. This could cut down unnecessary endoscopies by half.

Another promising area is DNA methylation testing. Researchers in Texas are funding a $2.4 million study to validate blood and tissue markers that predict cancer risk. If successful, future screening could be as simple as a blood test.

The Bottom Line

Barrett’s esophagus is a silent threat. It doesn’t scream. It whispers. And if you’ve had chronic GERD for over a decade, that whisper could be your body telling you something dangerous is happening.Don’t ignore frequent heartburn. Don’t assume it’s just stress or spicy food. If you’re a man over 50, white, overweight, or a smoker with daily reflux, talk to your doctor about screening. Early detection saves lives. Endoscopic ablation can remove precancerous tissue before it turns deadly.

And if you’ve already been diagnosed? Follow your surveillance plan. Stick to your PPIs. Make the lifestyle changes. Your esophagus doesn’t heal overnight-but with the right steps, you can stop it from turning into cancer.

Can Barrett’s esophagus go away on its own?

No, Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t reverse itself without treatment. The tissue change is permanent unless removed by endoscopic therapy like radiofrequency ablation. Even if your heartburn improves with medication, the abnormal cells remain. That’s why surveillance is necessary-even if you feel fine.

Is Barrett’s esophagus the same as esophageal cancer?

No. Barrett’s esophagus is a precancerous condition. It’s a change in the lining that increases your risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma, but most people with Barrett’s never get cancer. Only about 5% progress to cancer over their lifetime. Still, because esophageal cancer is aggressive and often caught late, monitoring Barrett’s is critical.

Do proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) cure Barrett’s esophagus?

No. PPIs reduce stomach acid and help with symptoms, but they don’t reverse the tissue changes in Barrett’s esophagus. Some studies show that even with daily PPI use, acid can still reach the esophagus. The goal isn’t just to feel better-it’s to stop the damage. That’s why lifestyle changes and surveillance are just as important as medication.

How often do I need an endoscopy if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

It depends on your biopsy results. For non-dysplastic Barrett’s, every 3-5 years. For low-grade dysplasia, every 6-12 months after confirmation by a specialist. High-grade dysplasia usually leads to treatment, not surveillance. After successful ablation, you’ll need yearly endoscopies for a few years, then possibly less often if no recurrence is found.

Can women get Barrett’s esophagus?

Yes, but it’s much less common. Men are three times more likely to develop it than women. Because of this, screening guidelines focus on men with multiple risk factors. Women with long-term GERD, especially those who are overweight or smoke, should still discuss screening with their doctor, especially if they have a family history of esophageal cancer.

What are the risks of endoscopic ablation?

Radiofrequency ablation and cryotherapy are generally safe, with serious complications occurring in less than 2% of cases. Possible side effects include chest pain, difficulty swallowing, or narrowing of the esophagus (stricture), which can usually be treated with dilation. The benefits of preventing cancer far outweigh these small risks, especially for patients with high-grade dysplasia.

Is there a blood test for Barrett’s esophagus?

Not yet for routine use. The current standard still requires endoscopy and biopsy. But new tests like TissueCypher analyze tissue samples for molecular markers to better predict cancer risk. Blood-based biomarkers are being researched, and a large study funded in 2023 aims to validate DNA methylation markers that could one day replace some endoscopies.

Ryan Anderson

November 13, 2025 AT 06:37Just got my endoscopy results back-non-dysplastic Barrett’s. Felt like a punch in the gut, but honestly? This post saved me. I’ve been on PPIs for 8 years and thought I was fine because my heartburn was ‘under control.’ Turns out, feeling okay doesn’t mean the damage isn’t there. Going to start sleeping with my bed elevated tonight. No more midnight pizza.

Kevin Wagner

November 14, 2025 AT 07:15Bro. This is the wake-up call America needs. I’m 52, white, obese, smoked for 20 years, and had daily reflux since I was 30. Three docs told me ‘it’s just acid’-until I read this. Got the endo last week. LGD confirmed. Started RFA next month. I’m not dying quietly. If you’ve got heartburn longer than your marriage, get checked. Your esophagus ain’t a joke.

gent wood

November 15, 2025 AT 06:39Thank you for this meticulously detailed and clinically accurate overview. I have been monitoring my own GERD symptoms for over a decade, and the distinction between symptom relief and mucosal healing is rarely emphasized in public discourse. The Seattle protocol’s rigor is often overlooked in community settings, and the emergence of TissueCypher represents a paradigm shift in risk stratification. I hope this reaches more primary care providers.

Scott Saleska

November 16, 2025 AT 00:19Everyone’s acting like this is some new revelation. I’ve had Barrett’s since 2017. You think PPIs fix it? Nah. I take 80mg a day and still get reflux. My doctor says ‘just keep monitoring.’ But I’ve seen three different endoscopy schedules in five years. One guy said every 2 years, another said 5, another said ‘if you feel worse.’ Who’s right? Nobody. This system is broken. And don’t even get me started on the cost. Insurance won’t cover the biopsy extras unless you’re ‘high risk.’ But what’s high risk? You tell me.

Eleanora Keene

November 17, 2025 AT 00:49Okay but can we talk about how insane it is that women are basically told to ‘wait and see’ unless they tick every box? I’m 48, had GERD since 25, BMI 32, mom had esophageal cancer. I asked for a scope. Was told ‘you’re not in the target group.’ I went private. Had Barrett’s. Non-dysplastic. But I’m still scared. Why are we making women prove they’re worthy of screening? 🤦♀️

Joe Goodrow

November 18, 2025 AT 20:33USA is soft. We treat heartburn like it’s a coffee habit. In my country, if you had this, you’d be in surgery by week two. We don’t wait for cancer to whisper. We shut it down. This post is good info but we need more action, not just ‘get screened.’ Get it cut out. Get it burned. Stop waiting for the system to catch up. Your body doesn’t care about your insurance plan.

Dilip Patel

November 18, 2025 AT 22:13Bro i had this and my doc said ppi will fix it so i just took it and ate spicy food every day. Now i got the biopsy and its like 5% chance of cancer so i dont care. Who cares if u get cancer? At least u lived. Also i dont believe in this barrett thing its just big pharma scam to sell scopes. I eat 3 pizzas a night and still run 5k. My body is a tank.

Jane Johnson

November 20, 2025 AT 16:36This post is alarmist. Most people with GERD never develop Barrett’s. Screening is overused. You’re scaring people into unnecessary procedures.

Don Ablett

November 22, 2025 AT 05:19While the clinical information presented is largely accurate, I must note that the 5.6% prevalence figure cited is drawn from a 2017 meta-analysis with significant geographic heterogeneity. The true prevalence in non-Caucasian populations remains under-researched, and the assumption that White males are the sole high-risk group may inadvertently delay diagnosis in other demographics. The TissueCypher assay, while promising, has yet to be validated in multi-center trials with longitudinal follow-up beyond three years. Caution in generalization is warranted.

Sean Evans

November 23, 2025 AT 02:48Let’s be real. This isn’t about health. It’s about money. Endoscopies cost $3k. RFA costs $15k. Insurance loves this. Doctors love this. Pharma loves this. And you? You’re just a walking wallet. I’ve got Barrett’s. I take omeprazole. I eat what I want. I’m 58. I’ve lived longer than my dad. You think your esophagus is fragile? It’s not. It’s been surviving your bad choices for decades. Stop paying for fear. Start living. 🤷♂️💊🔥