When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s not luck-it’s the result of one of the most tightly regulated processes in medicine. The FDA doesn’t just approve generics because they’re cheaper. It requires them to meet the same generic drug approval standards for safety, quality, and strength as the original drug. And the bar is higher than most people realize.

What Makes a Generic Drug Approved?

A generic drug isn’t just a copy. It’s a scientifically proven match. To get FDA approval, it must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and delivered the same way-whether it’s a pill, injection, or inhaler. It must also work the same way in your body. That’s not guesswork. It’s measured down to the last milligram and second of absorption.

The entire process runs through the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Unlike brand-name drugs, which need full clinical trials to prove they’re safe and effective, generics skip that step. Instead, they prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-name drug, called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). That means your body absorbs the generic at the same rate and to the same extent as the original. The FDA doesn’t accept "close enough." It demands proof.

Bioequivalence: The Core Requirement

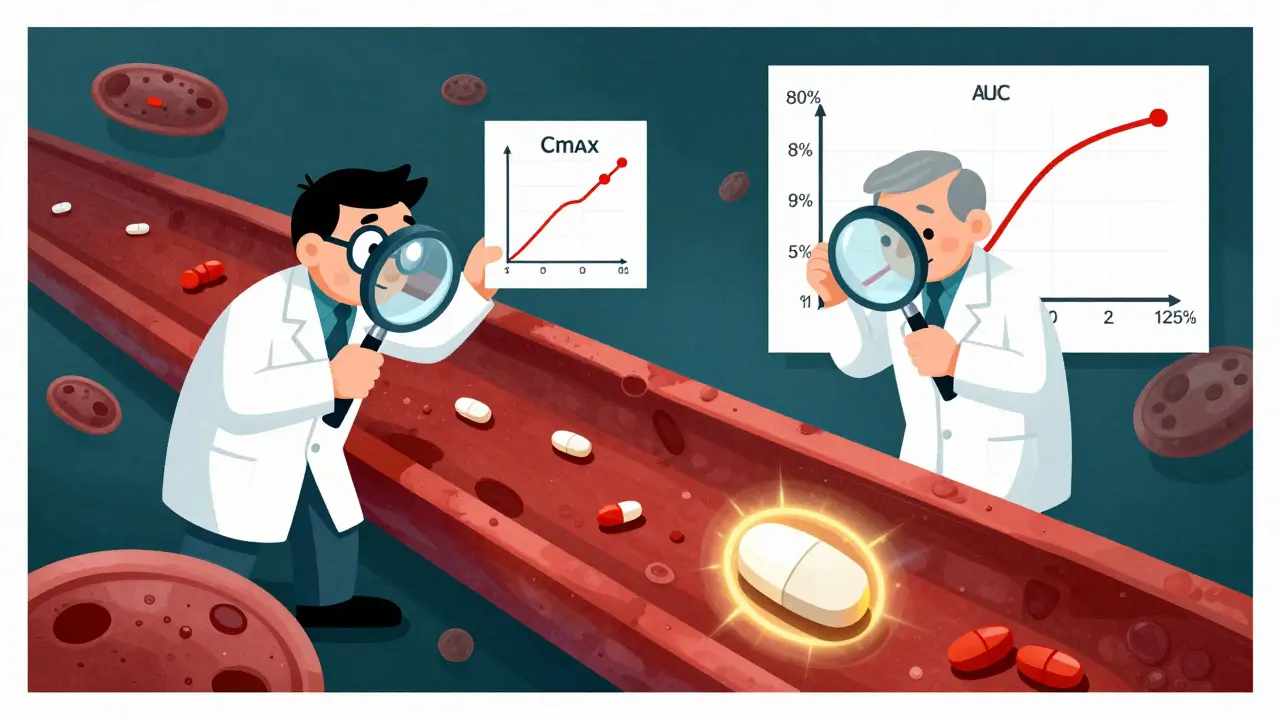

Bioequivalence is the make-or-break test. It’s done with blood tests in healthy volunteers. Researchers measure how much of the drug enters the bloodstream over time. Two key numbers are tracked: Cmax (the highest concentration) and AUC (how much drug is absorbed overall).

The FDA requires these numbers to fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s values. That’s a 45% range-but it’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of data showing that within this window, there’s no clinically meaningful difference in how the drug works. For most drugs, that’s fine. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or lithium-the rules tighten. For levothyroxine, the range is narrowed to 95%-105%. One extra milligram can throw off your thyroid levels. The FDA knows this. That’s why it sets stricter limits where it matters most.

Complex drugs like extended-release pills or inhalers need even more testing. A generic version of Ritalin LA, for example, must match the brand’s release pattern at three different time intervals: 0-3 hours, 3-7 hours, and 7-12 hours. If the drug releases too fast or too slow, it won’t work right. The FDA doesn’t just look at the total amount absorbed-it watches how it gets there.

Quality and Manufacturing: No Room for Error

A generic drug can be bioequivalent and still be unsafe if it’s poorly made. That’s why the FDA requires every manufacturer to follow Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). These rules cover everything: where the ingredients come from, how the pills are pressed, how the factory is cleaned, and how batches are tested.

Manufacturers must prove consistency. The FDA expects data from at least three consecutive commercial-scale batches showing the same hardness, dissolution rate, and purity. In 2021, Hetero Labs got a Complete Response Letter for its generic version of Jardiance because tablet hardness varied between batches. That’s not a minor issue. Uneven hardness can mean uneven drug release. One pill might release too much, another too little. The FDA won’t approve it until the problem is fixed.

Every facility is inspected before approval. The FDA conducts about 1,200 pre-approval inspections a year. If they find serious issues-like contaminated equipment, missing records, or unvalidated processes-the application is delayed. Many companies fail their first inspection. That’s why experienced teams matter. Successful ANDA submissions usually come from teams with at least five years of experience navigating these inspections.

Strength and Stability: It Has to Last

A generic drug must stay strong for its entire shelf life. That means it can’t break down too fast. The FDA requires stability testing under different conditions: heat, humidity, and light. The drug must still meet strength and purity standards after 24, 36, or even 60 months, depending on the label claim.

For example, if a generic version of a blood pressure pill claims a 36-month shelf life, the manufacturer must prove that after 36 months in a controlled environment, the active ingredient hasn’t degraded more than 5%. If it has, the expiration date gets shortened-or the product gets rejected.

This isn’t just paperwork. Real patients rely on this. If a generic pill loses potency in a hot car or a humid bathroom, it won’t work. The FDA’s standards ensure that doesn’t happen.

Why Do So Many Generics Get Rejected?

You’d think the abbreviated pathway would mean faster approvals. But the truth is, less than 10% of generic applications get approved on the first try. Why? Because the technical hurdles are massive.

Conventional pills-like generic ibuprofen or metformin-have a higher success rate. But complex products? That’s where things get messy. Inhalers, topical creams, injectables, and extended-release tablets are harder to copy. The device matters as much as the drug. The FDA approved only 3 out of 27 generic EpiPen applications between 2015 and 2020-not because the drug was wrong, but because the auto-injector mechanism didn’t match the original.

A 2021 DrugPatentWatch analysis showed that only 58% of complex generic applications were approved within three review cycles, compared to 76% for simple ones. The average approval time for a complex generic is nearly 47 months. For a standard pill, it’s about 28.5 months.

Many companies underestimate the depth of data needed. A typical ANDA is 5,000 to 10,000 pages long. It includes chemistry details, manufacturing processes, bioequivalence studies, and proposed labeling. Missing one form, mislabeling a batch number, or using the wrong solvent can trigger a rejection.

Cost and Speed: The Real Advantage

Despite the complexity, the generic pathway saves billions. Developing a brand-name drug costs about $2.6 billion. A generic? Around $1.3 million. That’s why 90% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics-but they make up only 23% of total drug spending.

The FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) help keep things moving. Under GDUFA, standard applications get reviewed in 10 months. Priority ones in 8. That’s faster than most people expect. And the FDA offers pre-ANDA meetings-1,200 a year-to help companies avoid mistakes before they submit.

Success often comes down to preparation. Companies that use the Pre-ANDA program are 32% more likely to get approved on the first try. They talk to the FDA early. They test their methods. They fix problems before they’re flagged.

Are Generics Really Safe?

Some patients worry. "Is this really the same?" The answer, backed by data, is yes. A 2021 report from the American Medical Association reviewed 15 years of post-market data and found that 98.7% of therapeutic categories showed no difference in outcomes between generics and brand-name drugs.

Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of the FDA’s drug center, put it simply: "Every approved generic meets the same rigorous standards as the brand-name drug, with no clinically meaningful differences in performance."

Even for drugs like levothyroxine-where small changes can matter-the FDA’s tighter limits and strict monitoring make generics safe. The key is consistency. If you switch from one generic to another, your doctor may monitor your levels more closely. But that’s not because generics are unreliable. It’s because switching between different manufacturers can introduce tiny variations in inactive ingredients, which may affect absorption in sensitive patients.

What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

The FDA is pushing to approve more complex generics. In 2023, it approved the first generic of Humira, a biologic drug with a complicated formulation. It also approved the first generic of Vivitrol, a monthly injectable for opioid addiction. These are milestones.

The agency’s 2023 GDUFA III plan aims to approve 50% of complex generics within two review cycles by 2027-up from just 28% today. That means more options for patients who need them.

But challenges remain. Patent thickets-where brand companies file dozens of minor patents to delay generics-still block access. The FTC found an average delay of 2.4 years between FDA approval and market entry because of lawsuits. That’s not a scientific problem. It’s a legal one.

Still, the system works. Generics save the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $1.7 trillion over the next decade. They’re not a compromise. They’re a carefully engineered solution to make medicine affordable without sacrificing safety or effectiveness.

Are generic drugs as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Every FDA-approved generic must prove it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This is called bioequivalence. Over 98% of therapeutic categories show no difference in clinical outcomes between generics and brand-name drugs, based on 15 years of post-market data reviewed by the American Medical Association.

Why do some people say generics don’t work for them?

Sometimes, it’s not the drug-it’s the switch. If you’ve been stable on one generic version and then switch to another made by a different company, minor differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or coatings) can slightly change how the drug is absorbed. This is most common with narrow therapeutic index drugs like thyroid medication or blood thinners. Your doctor may monitor your levels after a switch, but that doesn’t mean the generic is inferior-it just means your body is sensitive to small changes.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved?

For a standard pill, the process takes about 28.5 months on average from submission to approval. For complex drugs like inhalers or extended-release formulations, it can take nearly 47 months. The FDA aims to review standard applications within 10 months of submission, but most applications require multiple rounds of feedback before approval.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs, like pills or injections with one active ingredient. Biosimilars are copies of complex biological drugs made from living cells-like Humira or insulin. Because biological drugs are harder to replicate exactly, biosimilars require more clinical testing than generics. They’re not called generics because they’re not identical-they’re "similar enough" to be safe and effective.

Can I trust generics made overseas?

Yes. The FDA inspects all manufacturing facilities-whether they’re in the U.S., India, China, or elsewhere-before approving a generic. About 50% of generic drugs sold in the U.S. are made overseas, but every facility must meet the same cGMP standards. The FDA conducts thousands of inspections each year and has shut down plants for violations. If the FDA approves it, it meets U.S. safety and quality requirements.

Final Thoughts

The system isn’t perfect. It’s slow. It’s expensive to navigate. And some companies still struggle to meet the standards. But the result is clear: millions of people get the medicine they need at a fraction of the cost. The FDA doesn’t cut corners on safety or quality. It just cuts out the unnecessary steps. That’s the power of the generic approval process. It’s not about saving money-it’s about saving lives, without compromise.

Solomon Ahonsi

February 3, 2026 AT 06:15This whole FDA rigamarole is a joke. I’ve taken generics my whole life and half the time they don’t work right. My thyroid meds make me feel like a zombie one week and hyper as a squirrel the next. They’re not the same. Stop lying to us.

George Firican

February 3, 2026 AT 07:20The elegance of the FDA’s bioequivalence framework lies in its empirical humility. It doesn’t assume equivalence-it demands proof through pharmacokinetic rigor. The 80–125% window isn’t arbitrary; it’s a statistical envelope derived from decades of clinical outcomes, calibrated to exclude clinically significant variance. What’s astonishing is how rarely that envelope is breached in practice. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s one of the few places where science, not marketing, still holds the reins.

Matt W

February 4, 2026 AT 09:27I used to be skeptical too, but after my doc switched me from brand to generic for my blood pressure med and my numbers stayed rock solid for two years? I’m sold. The system works. People who say otherwise are either misattributing side effects or switching brands too often.

Anthony Massirman

February 5, 2026 AT 09:40Generics save lives. End of story.

Ansley Mayson

February 5, 2026 AT 23:11India makes most of these pills. You really think their factories are clean? The FDA inspects 1200 sites a year? That’s one per day. Good luck with that.

Hannah Gliane

February 7, 2026 AT 20:25Oh wow, so now we’re supposed to trust pills made in some basement in Bangalore because a government form says it’s "bioequivalent"? 🤡 I bet your grandma’s arthritis cream is just as good as the brand name. Just sayin’.

Nick Flake

February 8, 2026 AT 02:44This is the quiet miracle of modern medicine. Billions spent on brand-name R&D, then a thousand engineers and chemists quietly reverse-engineer it to make it affordable. No fanfare. No press releases. Just science doing its job. And yet we treat generics like second-class medicine. That’s not skepticism-it’s ingrained bias. The real tragedy isn’t the rejected applications-it’s the people who avoid generics out of fear. They’re paying more for the same thing. And that’s not smart. It’s sad.

Brett MacDonald

February 9, 2026 AT 12:23so like… if the generic is the same why do they cost so much less? like… are they just using cheaper sugar or something? also why do i feel weird on some brands but not others?

Monica Slypig

February 9, 2026 AT 13:07Of course the FDA approves them. They’re owned by the same pharma conglomerates. The whole system is rigged. You think they’d let a real competitor in? Please. The "bioequivalence" is a loophole. I’ve seen the data. It’s manipulated.

Becky M.

February 10, 2026 AT 07:34just wanted to say thank you for writing this. i’m from a country where generics are the only option and i’ve always been afraid to take them. reading this made me feel a lot better. also sorry for typos, typing on my phone in the car 😅

jay patel

February 11, 2026 AT 19:41bro the real story is how indian manufacturers like Dr. Reddy’s and Cipla are quietly revolutionizing global pharma. they’re not just copying-they’re innovating in formulation, packaging, distribution. you think the US could make 90% of its pills at 1/10th the cost? nah. we’re the ones outsourcing the real work. and yeah, sometimes the fillers change and you feel weird-but that’s not the drug’s fault. it’s your body adjusting. learn to adapt, not panic.

phara don

February 12, 2026 AT 20:41So if a generic passes bioequivalence, why do some people still report different side effects? Is it placebo? Or is there something the FDA misses?