When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, you might think generic versions hit the shelves right away. But that’s not how it works. In reality, it can take years after patent expiration before a generic version actually becomes available to patients. The gap between legal permission and real-world access isn’t a glitch-it’s built into the system. And understanding why helps explain why some medicines stay expensive long after they should’ve become affordable.

What Really Happens After a Patent Expires?

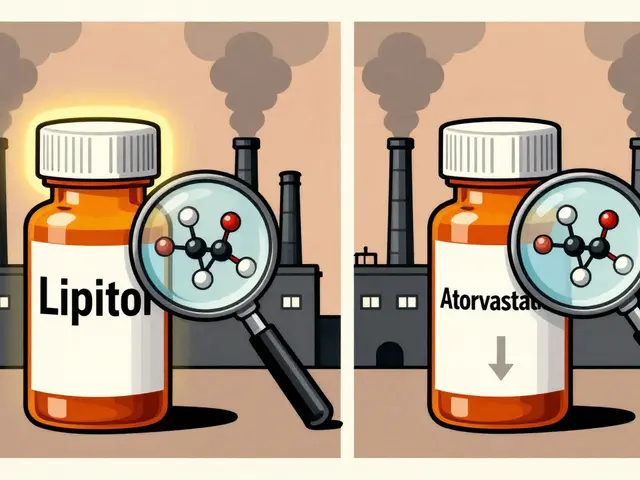

The 20-year patent clock for a drug starts ticking the moment the patent is filed, not when the drug hits the market. Since developing a new drug takes 8 to 10 years on average, companies often have only 7 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity before generics can legally enter. But that doesn’t mean generics show up the day after patent expiration. The real bottleneck isn’t the patent itself-it’s what happens next. The U.S. system for approving generics is built around the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This pathway lets generic manufacturers prove their version works just like the brand-name drug-without redoing expensive clinical trials. All they need to show is bioequivalence: the same active ingredient, same dose, same way it’s taken, and same effect in the body. Sounds simple, right? But the path to approval is anything but.The Hidden Layers of Protection

Brand-name drug makers don’t rely on just one patent. They build what experts call a “patent thicket.” A single drug might have dozens of patents covering different aspects: the active chemical, how it’s made, how it’s packaged, how it’s used for specific conditions, even how it’s delivered. The Orange Book, published by the FDA, lists every patent tied to a brand drug. According to research from UC Hastings, the average drug has 14.2 patents listed there. Each one can block a generic from launching-even if the main patent has expired. On top of patents, there are regulatory exclusivity periods that delay generic entry even further:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years-no generics allowed at all.

- New Clinical Investigation exclusivity: 3 years-for new uses or formulations.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years-for rare disease drugs.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to existing protections.

The 30-Month Stay and Patent Litigation

When a generic company files an ANDA and claims a patent is invalid or not infringed (called a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name company can sue. If they do, the FDA is legally required to delay approval for up to 30 months. That’s called the 30-month stay. But here’s the twist: studies show this stay rarely causes the biggest delays. In fact, the median time between the end of the 30-month stay and actual generic launch is over 3 years. Why? Because lawsuits drag on. Court cases can take 37 months just to reach a final decision. And even when a generic wins, manufacturers still need time to ramp up production. What’s worse? Many of these lawsuits end in secret settlements. The FTC found that 55% of delayed generic entries come from “reverse payment” deals-where the brand-name company pays the generic maker to stay out of the market. The Supreme Court ruled these illegal in 2021, but they still happen. A 2022 Congressional Research Service report showed these settlements delay entry by an average of 2.1 years.

Why Some Generics Take Longer Than Others

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to generic entry. Small molecule drugs-pills you swallow-usually see generics arrive within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But complex drugs? That’s a different story. Biologics, like insulin or cancer treatments made from living cells, follow a different approval path under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). These can take 4.7 years on average to reach the market after patent expiration. Why? Because they’re harder to copy. You can’t just replicate a living cell’s behavior like you can a chemical compound. The FDA calls them “complex generics,” and they take longer to test, manufacture, and approve. Even within small molecules, some categories are slower. Cardiovascular drugs face delays averaging 3.4 years post-patent, while dermatological products get generics in as fast as 1.2 years. Why? It’s often about how many patents are stacked on top of each other. Drugs with over 10 Orange Book-listed patents take 37% longer to enter the market.The First-Mover Advantage (and Its Pitfalls)

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets a special reward: 180 days of exclusive market access. That means no other generic can enter during that time. It’s a huge incentive. But it’s also a trap. To keep that exclusivity, the first filer must launch within 75 days of FDA approval. That’s a tight window. Many companies rush production, cut corners, and end up with quality issues. FDA data shows 22% of first filers forfeit their exclusivity because they can’t get their manufacturing right. Another 10% lose it because of legal setbacks. Only 68% successfully launch on time. The smartest companies prepare for this. Sandoz, for example, developed 3 to 4 backup manufacturing processes for its generic version of Copaxone. That way, if one process got blocked by a patent challenge, they could switch instantly. It’s expensive, but it’s the only way to win the race.