Every year, Americans spend over $400 billion on prescription drugs. About 90% of those prescriptions are for generic medications - but getting there wasn’t automatic. States didn’t just wait for doctors and patients to choose generics on their own. They built systems to make it easier, cheaper, and sometimes even mandatory. These systems - called generic prescribing incentives - are now the backbone of state-level efforts to control drug spending without sacrificing care.

How States Push Doctors and Pharmacies Toward Generics

States don’t rely on goodwill. They use real financial levers. The most common tool? Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). These are lists of generic drugs that Medicaid and other state programs will cover with the lowest out-of-pocket cost. If a doctor prescribes a brand-name drug that’s not on the list, the patient often pays more - or the prescriber has to jump through hoops to get approval. As of 2019, 46 out of 50 states had PDLs. In 29 of those states, Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees - made up of doctors, pharmacists, and sometimes patients - decide which drugs make the list. These committees don’t just pick based on price. They look at clinical data, safety, and whether the generic works just as well as the brand. But price matters. A lot. Because for every dollar saved on a prescription, the state saves more when you factor in Medicaid’s rebate system.The Hidden Money: Medicaid Rebates and Why Generics Win

The federal government started the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program in 1990. It requires drug makers to give states a cut of what they charge. For brand-name drugs, that’s at least 23.1% of the average price. For generics? It’s 13%. Sounds low? Here’s the catch: generics cost far less to begin with. So even a smaller percentage adds up fast. States don’t stop there. Most of them negotiate extra rebates on top of the federal minimum. In 2019, 46 states had supplemental rebate deals with generic manufacturers. That’s why a $5 generic might end up costing the state only $1.50 after rebates. That’s the real savings engine. Meanwhile, brand-name companies often offer rebates too - but they’re not always passed on to patients. Sometimes, the rebate goes to the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), not the state. That’s why PDLs are so powerful: they cut through the middlemen and put the cheapest, proven option first.Pharmacist Substitution: The Silent Game-Changer

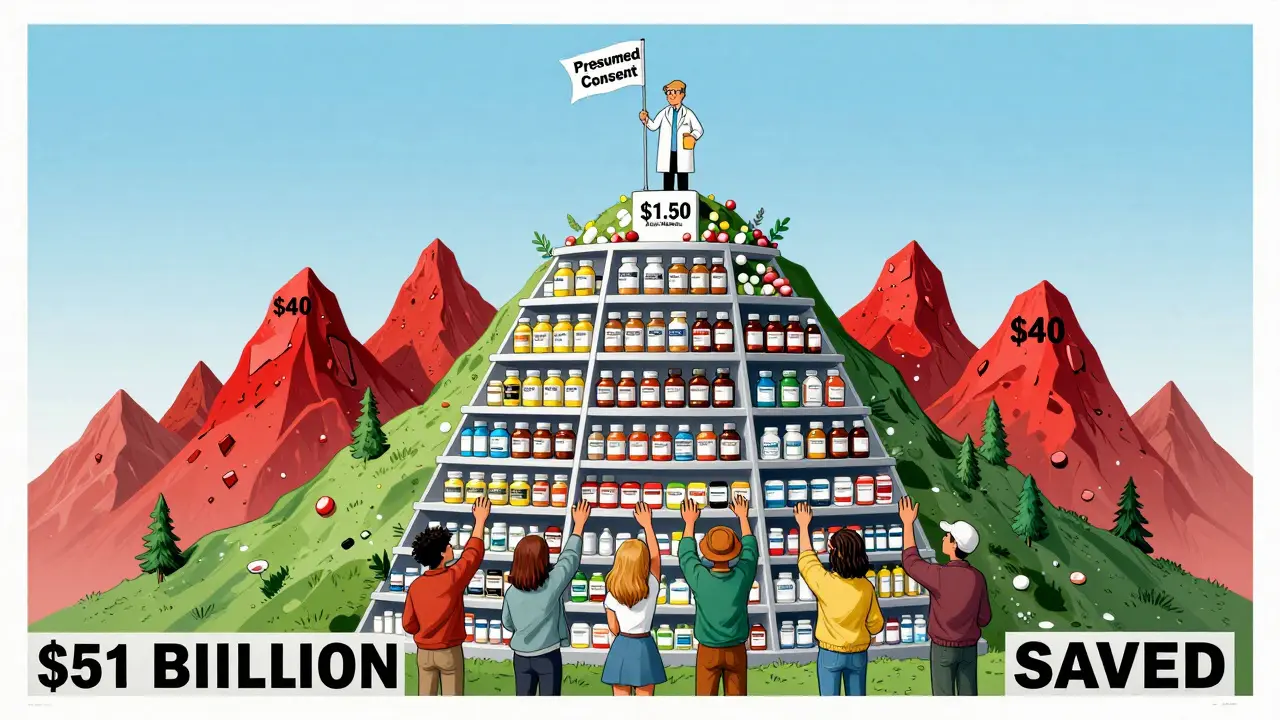

Here’s something most people don’t realize: your pharmacist can switch your brand-name drug for a generic - without asking you - in most states. That’s called presumed consent. It means if you show up with a prescription for Lipitor, and there’s a generic version of atorvastatin available, the pharmacist can fill it as the generic unless you say no. In 39 states, this is the default. In the other 11, pharmacists must ask you first - explicit consent. The difference? Huge. A 2018 NIH study found that presumed consent laws boosted generic dispensing by 3.2 percentage points. That might not sound like much, but it translates to $51 billion in annual savings across those 39 states. Why does this work better than laws forcing substitution? Because pharmacists already have a profit motive. They make more money dispensing generics. So even without a law, many do it anyway. But when you remove the need to ask the patient, you cut down on hesitation, confusion, and delays. The patient gets the cheaper drug. The state saves money. Everyone wins - except maybe the brand-name company.

Copay Differentials: Making Patients Feel the Difference

The most direct way to push people toward generics? Make them pay less for them. That’s what copay differentials do. In many states, a 30-day supply of a brand-name drug might cost $40. The generic? $10. That’s a $30 difference - and it’s not just a suggestion. It’s a financial nudge. Back in the late 1990s, the gap between brand and generic dispensing fees for pharmacies was just 8 cents. But copay differentials kept growing. Why? Because states realized: if you want behavior change, make it hurt less to choose the generic. Patients aren’t price-sensitive because they’re cheap - they’re price-sensitive because they’re paying out of pocket. And when they see a $30 savings, they notice. As of 2022, only 15 states and Puerto Rico had formal laws requiring these copay differences. But even in states without laws, many Medicaid programs and private insurers still use them. The effect? Patients switch. Studies show that when copays for generics are under $10, adherence improves - meaning people actually take their meds, not just fill the prescription.Why Some States Struggle - And Why Generics Still Disappear

It sounds simple: make generics cheaper, and everyone uses them. But the market isn’t that straightforward. Generic manufacturers sometimes get caught in a trap. Medicaid’s inflation rebate formula ties payments to the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U). But if the cost of raw ingredients spikes - or if there’s a shortage - the generic maker’s costs go up. But Medicaid won’t raise the rebate unless the brand-name version’s price goes up too. So the generic becomes unprofitable. Avalere Health found five scenarios where this happens - and in each case, the result is the same: the generic gets pulled from the market. Suddenly, the state’s favorite low-cost option vanishes. Patients are forced back to the brand. Costs spike. And the state has to scramble to find a replacement - if one even exists. This is why some states are now pushing for more transparency. They want to know not just the price of the drug, but what it costs to make it. They’re also watching the 340B program, which lets safety-net hospitals buy drugs at steep discounts. But reimbursement rules for those drugs are messy. In 2016, CMS said states can’t reimburse pharmacies more than the 340B ceiling price. That sounds fair - until a pharmacy loses money on every generic it dispenses.

The Future: A Drug List for Everyone?

The federal government is watching. CMS is testing a new idea: a $2 Drug List for Medicare Part D. It would make a set of low-cost generics - like metformin, lisinopril, and levothyroxine - available for just $2 a month, no matter your plan. No prior authorization. No formulary restrictions. Just $2. It’s still in development, but if it works, states will likely copy it. Why? Because it removes complexity. Patients don’t need to understand PDLs or copay tiers. They just get the drug they need - cheaply and predictably. States are already moving toward simpler models. The old days of 20-page formularies and 12-step prior auth processes are fading. What’s rising? Transparency. Predictability. And real savings.What Works - And What Doesn’t

Let’s cut through the noise. Based on real data:- Presumed consent laws work best - they’re the most effective single policy.

- Preferred Drug Lists are the most widely used - but they only work if the state actually updates them regularly. Some states review theirs once a year. Others do it quarterly. The ones that update fast see bigger savings.

- Copay differentials drive patient behavior - and they’re the most visible incentive to the public.

- Mandatory substitution laws (forcing pharmacists to switch) don’t do much - because pharmacists were already doing it.

- Penalizing pharmacists for dispensing brands? Doesn’t work. Pharmacists aren’t the problem. The system is.

What Comes Next?

States aren’t done. With drug prices still climbing and budgets tightening, they’re looking at new tools: real-time price alerts for prescribers, automatic generic switches for chronic meds, and even public dashboards showing which drugs are saving the most money. But the biggest challenge isn’t policy. It’s sustainability. If the market keeps pushing generics out because of broken rebate rules, then all the incentives in the world won’t matter. The goal isn’t just to use more generics. It’s to make sure they’re always there.What are Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) and how do they work?

Preferred Drug Lists are state-maintained catalogs of medications - mostly generics - that Medicaid and other public programs cover at the lowest cost. If a doctor prescribes a drug not on the list, the patient may pay more, or the prescriber must get prior authorization. These lists are updated regularly by pharmacy experts and are used in 46 states to steer prescribing toward lower-cost, equally effective options.

Do pharmacists need my permission to give me a generic drug?

In 39 states, pharmacists can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug without asking you - this is called presumed consent. In the other 11 states, they must get your permission first (explicit consent). Studies show presumed consent increases generic use by over 3 percentage points because it removes delays and confusion.

Why are generic drugs cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs cost less because they don’t require the same expensive clinical trials as brand-name drugs. Once a brand’s patent expires, other companies can make the same drug using the same active ingredient. They don’t need to pay for research, marketing, or advertising - so they can sell it for a fraction of the price. Medicaid and other programs then negotiate even lower prices through rebate programs.

Why do some generic drugs disappear from the market?

Some generic manufacturers stop making drugs because Medicaid’s rebate formula doesn’t account for rising production costs. If ingredient prices spike or there’s a shortage, but the brand-name drug’s price doesn’t go up, the generic maker can’t raise its price - but still has to pay the same rebate. This can make the drug unprofitable, leading to withdrawal. Five specific scenarios cause this, according to Avalere Health.

Is the $2 Drug List a state program?

No, the $2 Drug List is a federal Medicare Part D proposal by CMS. It would make a set of low-cost generics available for just $2 per month to Medicare beneficiaries. States are watching closely and may adopt similar models for their Medicaid programs if the federal version proves effective and sustainable.

kabir das

January 30, 2026 AT 09:02Wow, this is insane-seriously, who thought up these systems?? I mean, $51 BILLION in savings just from letting pharmacists swap drugs without asking?? And we’re still arguing about whether people should be able to choose their meds?? I’m not even mad-I’m impressed. Like, who even needs brand names anymore??

Keith Oliver

January 31, 2026 AT 06:23Let’s be real-this whole ‘generic incentive’ thing is just corporate welfare dressed up as public health. You think these PDLs are about savings? Nah. They’re about squeezing every last penny out of patients while Big Pharma quietly raises prices on the 10% of drugs that still have patents. And don’t get me started on PBMs-they’re the real parasites here. The system’s rigged, and this is just the sanitized version they want you to believe in.

Kacey Yates

January 31, 2026 AT 20:07Presumed consent laws are the only thing that actually works. No one cares about the 3.2% bump-it’s the fact that people actually take their meds that matters. Stop overcomplicating it. Just let the pharmacist do their job. Also, typo: ‘atovastatin’ should be ‘atorvastatin’-but you get the point.

DHARMAN CHELLANI

February 2, 2026 AT 00:48Generics? Please. Most of them are made in China with ingredients that would make your grandma cry. This whole ‘savings’ narrative is just a distraction from the real problem: we’ve outsourced our medicine to a country that doesn’t even have FDA oversight. And now you want us to trust these pills? Lol.

ryan Sifontes

February 2, 2026 AT 20:29So… what if the ‘savings’ are just a front? What if the real goal is to force people into cheaper meds so insurance companies can profit more? I’ve seen people skip doses because even $10 is too much. This isn’t saving lives-it’s just shifting the burden. And don’t even get me started on the 340B program. It’s all smoke and mirrors.

Robin Keith

February 3, 2026 AT 19:55It’s fascinating, isn’t it? The entire architecture of pharmaceutical policy is built on the quiet, unspoken assumption that human beings are rational economic agents-when in reality, we’re emotional, irrational, terrified creatures who will pay $200 for a pill if it makes us feel safe. The PDLs, the copay differentials, the presumed consent-they’re all just behavioral nudges, psychological levers pulled by bureaucrats who’ve read too much Thaler. But here’s the real tragedy: we’ve turned healthcare into a game of incentives, and forgotten that people aren’t data points-they’re suffering beings trying to stay alive. And we’re optimizing for cost, not compassion.

Sheryl Dhlamini

February 5, 2026 AT 05:03Okay but-can we just take a second to appreciate how wild it is that a pharmacist can swap your medicine without asking? Like… that’s kind of terrifying and kind of beautiful at the same time. I didn’t even know this was a thing. I’m gonna go tell my mom. She’s on blood pressure meds and has no idea.

Doug Gray

February 6, 2026 AT 13:38It’s a classic principal-agent problem, really. The prescriber (agent) is incentivized to prescribe based on familiarity or pharma reps, not cost-effectiveness. The payer (principal) tries to realign incentives via PDLs and copay differentials-but the PBM layer introduces agency drift. The 340B ceiling price cap exacerbates this by creating negative margins for safety-net pharmacies. The $2 Drug List is a band-aid on a hemorrhage. What we need is a single-payer reimbursement model that decouples formulary decisions from profit motives. Until then, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

LOUIS YOUANES

February 6, 2026 AT 16:16Generic drugs are fine, I guess. But you ever notice how the ones that disappear are always the ones you’ve been on for 10 years? Like, you get stable, then BAM-no more atorvastatin. And suddenly you’re back to Lipitor at $400 a month. Yeah, ‘savings’ my ass. This whole system is just a giant game of musical chairs and we’re all stuck without a chair when the music stops.

Alex Flores Gomez

February 6, 2026 AT 23:46Yall act like generics are some magic bullet. But what about bioequivalence? Some generics are just… not the same. I’ve had my thyroid meds switch and suddenly I’m a zombie. You can’t just treat all generics like they’re interchangeable. The system’s broken because it assumes biology is a spreadsheet.

Frank Declemij

February 7, 2026 AT 02:19This is the most practical healthcare policy I’ve seen in years. Simple, transparent, and actually works. No drama. No lobbying. Just letting pharmacists do what they’re trained to do and letting patients save money. Why isn’t this federal already?