Ever wonder why a pill you swallow can calm your nerves, lower your blood pressure, or kill an infection - all without touching the place where you feel the problem? It’s not magic. It’s chemistry. And understanding how medicines work isn’t just for doctors. It’s the key to using them safely - and knowing when something’s going wrong.

How Medicines Actually Work

Medicines don’t float around your body looking for trouble. They’re designed to fit into specific spots, like a key into a lock. These spots are called receptors, and they’re found on cells all over your body - in your brain, heart, liver, even your gut. When a medicine fits just right, it either turns the cell on (an agonist) or blocks it (an antagonist). Take aspirin. It doesn’t just ‘reduce pain.’ It blocks an enzyme called COX-1, which your body uses to make chemicals that cause pain and swelling. No enzyme, no pain signal. That’s why it works for headaches, but won’t help with a bacterial infection. Antibiotics like penicillin work differently. They attack the walls of bacteria, making them burst. Your cells don’t have those walls, so they’re left alone. Some medicines, like SSRIs (such as fluoxetine or Prozac), work by stopping your brain from reabsorbing serotonin - a chemical linked to mood. Think of it like putting a cork in a recycling tube. Serotonin stays in the space between nerve cells longer, helping signals get through. That’s why these drugs take weeks to work - your brain needs time to adjust. Not all medicines reach their target easily. If you swallow a pill, it has to survive your stomach acid, get absorbed through your gut, and then make it past your liver, which can break down up to 90% of some drugs before they even get into your bloodstream. That’s called the first-pass effect. That’s why some pills are given as injections or patches - they bypass this filter.Why Protein Binding Matters

Once a medicine gets into your blood, about 95 to 98% of it sticks to proteins like albumin. That’s not a problem - until it is. Only the small, unbound portion can actually interact with your cells. If another drug comes along and kicks the first one off those proteins, suddenly you’ve got a lot more active medicine floating around. That’s why mixing warfarin (a blood thinner) with certain antibiotics or even some painkillers can turn a safe dose into a dangerous one. Warfarin is 99% protein-bound. Even a 10% displacement can push free warfarin levels up by 20-30%. That’s enough to cause dangerous bleeding. That’s not a guess. It’s a documented risk, and it’s why pharmacists ask you about every supplement and over-the-counter pill you take.The Blood-Brain Barrier and Special Delivery

Your brain is protected by a tight filter called the blood-brain barrier. Most drugs can’t get through. That’s good - it keeps toxins out. But it’s a problem if you need to treat Parkinson’s, epilepsy, or depression. That’s why drugs like Sinemet (levodopa + carbidopa) were engineered. Levodopa is a chemical your brain turns into dopamine. But it can’t cross the barrier on its own. Carbidopa helps it slip through by blocking enzymes that would break it down too early. Without this trick, Parkinson’s treatment wouldn’t work.

When Medications Are Safe to Use

Safety isn’t just about avoiding overdoses. It’s about matching the right drug to the right person, at the right time, with the right monitoring. Take lithium for bipolar disorder. It’s effective - but the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny. Blood levels must stay between 0.6 and 1.2 mmol/L. Too low? No effect. Too high? Tremors, confusion, kidney damage. That’s why people on lithium get regular blood tests. It’s not routine - it’s life-saving. Another example: statins for cholesterol. They block an enzyme (HMG-CoA reductase) that makes cholesterol in your liver. But they can also cause muscle damage. The key? Monitoring. If you start a statin and feel unexplained muscle pain, you report it. Why? Because the mechanism is known. The risk is real. And catching it early prevents rhabdomyolysis - a rare but deadly breakdown of muscle tissue. Studies show patients who understand how their statin works are over three times more likely to report muscle pain early. That’s not coincidence. It’s knowledge saving lives.Drug Interactions You Can’t Ignore

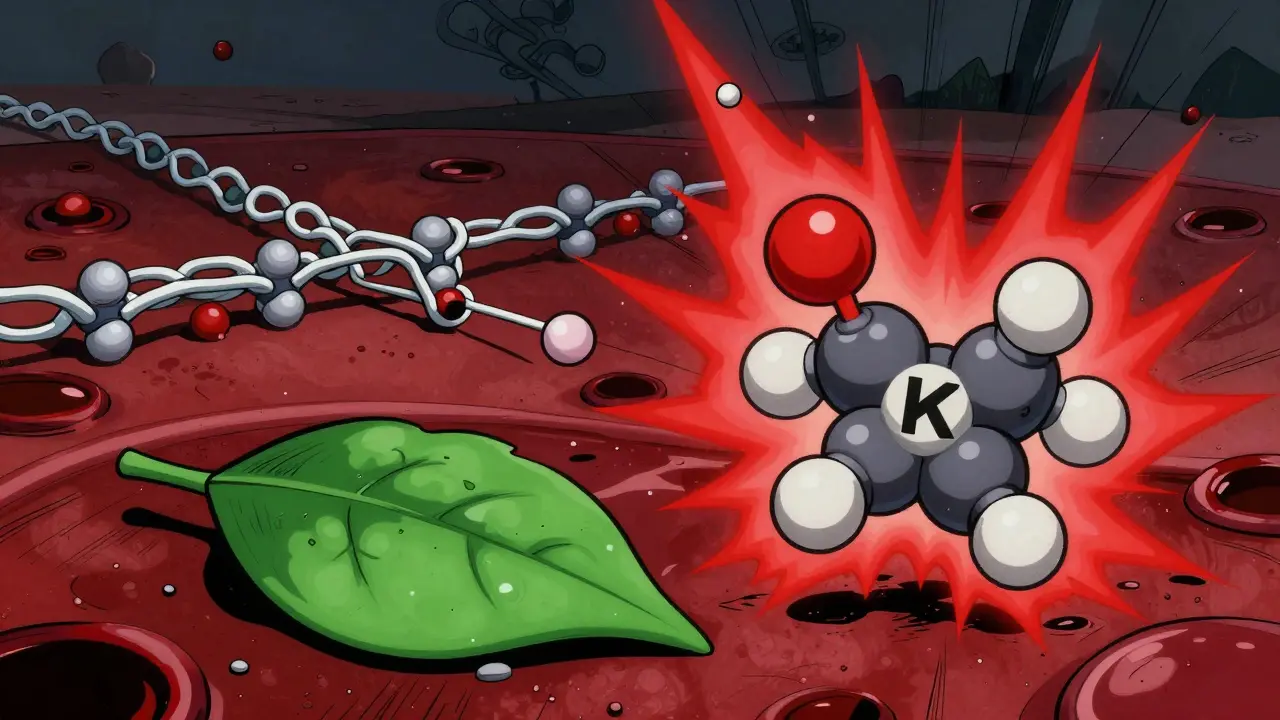

Some interactions are obvious. Like mixing alcohol with sedatives. Others are sneaky. If you’re on an MAO inhibitor (used for depression), eating aged cheese, cured meats, or tap beer can cause a sudden, dangerous spike in blood pressure. Why? These foods contain tyramine. MAO inhibitors block the enzyme that breaks down tyramine. So it builds up - and your blood pressure rockets. One ounce of blue cheese can have 1-5 mg of tyramine. Enough to trigger a hypertensive crisis. Or take warfarin and green vegetables. Kale, spinach, broccoli - they’re full of vitamin K, which helps your blood clot. Warfarin works by blocking vitamin K. If you suddenly eat a salad every day, your INR (a blood test that measures clotting time) drops. You’re not protected from clots anymore. If you stop eating greens, your INR spikes. You could bleed internally. That’s why patients on warfarin are told to keep their vitamin K intake steady - not avoid it, but keep it consistent.Why Your Genetics Matter

You and your neighbor might take the same pill. But your bodies handle it differently. Your genes control how fast your liver breaks down drugs. Some people are fast metabolizers - the drug vanishes before it can work. Others are slow - the drug builds up and causes side effects. The NIH’s All of Us program found that 28% of bad drug reactions are tied to genetic differences. For example, a common gene variant (CYP2D6) affects how 25% of all prescription drugs are processed. If you’re a slow metabolizer and take codeine, your body turns it into morphine too slowly - you get no pain relief. If you’re ultra-rapid, you turn it into morphine too fast - you risk overdose. This isn’t science fiction. Genetic testing for drug metabolism is already being used in cancer care and psychiatry. It’s the future - and it’s here.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

You don’t need a medical degree to use medicines safely. But you do need to ask questions.- Ask your doctor or pharmacist: ‘How does this medicine work?’ and ‘What should I watch out for?’

- Know the side effects tied to its mechanism. If your statin blocks cholesterol production, muscle pain is a red flag. If your SSRI blocks serotonin reuptake, don’t stop it cold turkey - you could get dizziness, nausea, or electric-shock sensations.

- Keep a list of everything you take. Including vitamins, herbal supplements, and OTC painkillers. Many interactions happen with ‘harmless’ stuff.

- Don’t assume natural means safe. St. John’s Wort can make birth control fail. Grapefruit can turn a normal dose of a blood pressure pill into a dangerous one.

- Use visual aids. Pharmacists who use diagrams of drug-receptor interactions see a 42% improvement in patient understanding. Ask for one.

The Bigger Picture

The global market for tracking drug safety is growing fast - from $6.8 billion in 2022 to over $14 billion by 2029. Why? Because we’re learning that safety isn’t just about labels and warnings. It’s about understanding the science behind the pill. Drugs with well-understood mechanisms - like direct oral anticoagulants that block specific clotting factors - are adopted faster by doctors because their risks are predictable. Drugs with fuzzy mechanisms? They’re more likely to be pulled from the market later. The FDA now requires detailed mechanism-of-action data for 87% of new drugs - up from 62% in 2015. That’s progress. And it means the medicines you’re prescribed today are being built with safety in mind - if you know how to use them.Final Thought

Medicines are powerful tools. But they’re not harmless. They’re chemicals - and chemicals follow rules. When you understand those rules, you stop being a passive recipient of a pill. You become an active partner in your care. That’s not just safer. It’s empowering.How do medicines know where to go in the body?

Medicines don’t ‘know’ where to go. They travel through the bloodstream and interact with cells that have the right receptors - like a key fitting into a lock. Only cells with those specific receptors respond. That’s why a painkiller doesn’t affect your stomach lining the same way it affects your brain, and why antibiotics target bacteria but not human cells.

Can I stop taking my medicine if I feel better?

It depends. For antibiotics, stopping early can let resistant bacteria survive and come back stronger. For antidepressants like SSRIs, stopping suddenly can cause withdrawal symptoms because your brain has adjusted to higher serotonin levels. For blood pressure or cholesterol meds, stopping can cause your condition to rebound. Always talk to your doctor before stopping - even if you feel fine.

Why do some medicines have so many side effects?

Because most drugs don’t target just one spot. Lithium, for example, affects multiple brain chemicals and kidney function. Statins can affect muscles because the same enzyme they block in the liver is also involved in muscle cell energy. The more a drug interacts with different systems, the more side effects it can cause. That’s why newer drugs are designed to be more selective - to hit only the target.

Are natural supplements safer than prescription drugs?

No. Just because something is natural doesn’t mean it’s safe. St. John’s Wort can interfere with birth control, antidepressants, and heart medications. Garlic supplements can thin your blood like aspirin. Kava can damage your liver. Supplements aren’t tested the same way as prescription drugs, so their interactions and risks are often unknown.

What should I do if I think a medicine is causing a side effect?

Don’t ignore it. Write down what you’re feeling, when it started, and what else you’re taking. Call your doctor or pharmacist. If it’s serious - like chest pain, trouble breathing, swelling, or severe rash - go to an emergency room. Many side effects are mild and go away, but some are warning signs. Knowing your drug’s mechanism helps you recognize which symptoms matter.

Why do I need blood tests while on some medicines?

Because some drugs have a narrow safety window. Lithium, warfarin, and certain seizure meds can be effective at one level and toxic at just a little higher. Blood tests measure how much of the drug is in your system. It’s not about checking if it’s working - it’s about making sure it’s not poisoning you.

Ted Conerly

January 11, 2026 AT 08:01Understanding how drugs bind to receptors is the foundation of safe prescribing. That key-and-lock analogy isn’t just cute-it’s why we don’t give antibiotics for viral infections. The mechanism dictates the outcome. If you don’t get that, you’re just gambling with your health.

And yes, the first-pass effect is brutal. That’s why sublingual nitroglycerin works for angina-bypasses the liver, hits the bloodstream fast. No guesswork. Just chemistry.

Ian Cheung

January 13, 2026 AT 05:18people think pills are magic beans but nope its just biochemistry playing chess inside your body

one wrong move and boom your liver is throwing a tantrum

st johns wort is basically a sneaky saboteur in your drug metabolism system

Lisa Cozad

January 14, 2026 AT 06:04I’ve been on SSRIs for six years and this is the first time someone explained why the withdrawal feels like electric shocks. It’s not ‘just in my head’-my neurons are literally scrambling to readjust. Thank you for making this clear.

Also, I started tracking my vitamin K intake after my INR went haywire. Kale isn’t the enemy. Inconsistency is.

Saumya Roy Chaudhuri

January 16, 2026 AT 04:39Oh please. You think genetic testing for CYP2D6 is ‘the future’? It’s 2024. We’ve known about poor vs ultra-rapid metabolizers since the 90s. The fact that most doctors still don’t test is criminal negligence. Your statin isn’t ‘working’-it’s just not being broken down fast enough because you’re a slow metabolizer. Blame your DNA, not your pharmacist.

Mario Bros

January 16, 2026 AT 08:53bro i took ibuprofen with grapefruit juice once and felt like my heart was trying to escape my chest

now i just read the label. no cap.

Jay Amparo

January 18, 2026 AT 01:16This is one of the clearest explanations of pharmacology I’ve ever seen. I’m from India, and here, people pop antibiotics like candy. My cousin took ciprofloxacin for a cold-then got tendon rupture. No one told him about the risks. We need more of this education.

Even my aunt thinks ‘natural’ means ‘no side effects.’ I showed her the liver damage reports on kava. She now asks her doctor before taking ashwagandha. Small wins.

anthony martinez

January 19, 2026 AT 10:37Let’s be real-the whole ‘ask your doctor’ advice is useless if your doctor doesn’t know either. I’ve had three different physicians tell me conflicting things about warfarin and spinach. One said ‘avoid it.’ One said ‘eat it daily.’ One said ‘whatever, just get your INR checked.’

Turns out, the last one was right. But why should I have to become a pharmacologist to not die?

Dwayne Dickson

January 19, 2026 AT 15:26It is not merely a matter of biochemical affinity or pharmacokinetic profiles; rather, it is a profound epistemological imperative that patients comprehend the mechanistic underpinnings of their therapeutic regimens. The reductionist paradigm of ‘take one pill, feel better’ is not only scientifically bankrupt-it is ethically indefensible in an era of precision medicine.

Consider the case of levodopa: its efficacy is entirely contingent upon the co-administration of carbidopa, which inhibits peripheral decarboxylation-a phenomenon that, if unaccounted for, renders the entire therapeutic endeavor inert. This is not pharmacology. This is molecular choreography.

And yet, the lay public persists in treating pharmaceuticals as if they were enchanted talismans. The blood-brain barrier is not a suggestion. It is a biological firewall. To misunderstand it is to court iatrogenic catastrophe.

Moreover, the protein-binding displacement phenomenon-exemplified by warfarin and fluconazole-is not a footnote in a textbook. It is a clinical grenade. A 10% displacement yields a 20–30% surge in free drug concentration. That is not ‘a risk.’ That is a mathematical certainty of hemorrhage.

One must ask: if a patient cannot parse the difference between an agonist and an antagonist, how can they be entrusted with their own physiology? The answer, regrettably, is that they cannot. And yet, we continue to prescribe.

Christine Milne

January 20, 2026 AT 00:19Of course, this entire article assumes American medical standards are universally applicable. In countries with functional healthcare systems, drug safety is not left to the whims of patient ‘understanding.’ It’s regulated, monitored, and enforced by trained professionals-not by blog posts and visual aids.

Also, the NIH’s ‘All of Us’ program is a $2 billion boondoggle. We don’t need genetic testing to know that mixing alcohol and benzodiazepines kills people. Basic common sense should suffice. Why are we outsourcing responsibility to DNA?

Faith Edwards

January 21, 2026 AT 21:52How quaint. You’ve written a 2,000-word essay on pharmacokinetics and called it ‘empowering.’

Meanwhile, millions of people in this country can’t afford their prescriptions, and you’re lecturing them about serotonin reuptake and CYP2D6 polymorphisms like it’s a TED Talk at a private university.

Let me guess-you’ve never waited three weeks for a Medicaid approval just to get your lithium levels checked. You think ‘knowledge is power’? Try telling that to the single mother who skips doses because the co-pay is $120 and her kid needs shoes.

Medicine isn’t a puzzle to be solved with diagrams. It’s a system rigged to profit from ignorance. And you’re just polishing the brass on the Titanic while the water rises.

Jake Nunez

January 22, 2026 AT 19:49My grandfather took digoxin for 15 years. Never had a blood test. Never had a genetic screen. Lived to 92. He just took it when the nurse came. No questions. No charts. No apps.

Maybe the real lesson isn’t about receptors or protein binding.

Maybe it’s about trust.

And the fact that we’ve turned something simple into a PhD thesis is the real problem.