When you're on Medicaid, getting your generic prescriptions shouldn't be a mystery-but in reality, it often feels like one. What’s covered in Colorado might be denied in Texas. What’s free in California could cost you $8 in Ohio. The truth is, Medicaid generic coverage isn’t one national rule. It’s 51 different systems-each with its own list of approved drugs, copays, step therapy rules, and paperwork hoops. If you’ve ever been told your generic wasn’t covered, or had to wait days for approval, you’re not alone. You’re just caught in the middle of a patchwork system that’s trying to balance cost, access, and clinical safety.

How Medicaid Generic Coverage Works (The Federal Baseline)

Federal law doesn’t require states to cover prescription drugs under Medicaid-but every single state does. Why? Because the financial incentives are too strong to pass up. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, started in 1990, forces drug makers to pay rebates to states in exchange for having their drugs included on Medicaid formularies. For generic drugs, those rebates can be huge. In 2024, generic prescriptions made up 84.7% of all Medicaid drug claims but only cost 28.3% of the total pharmacy budget. That’s the math that keeps states offering coverage.

But here’s the catch: federal law only says states can cover drugs. It doesn’t say how. That’s why states get to decide which generics go on their preferred lists, which ones need prior authorization, and how much patients pay out of pocket. The only federal guardrails are a few drugs that are banned outright-like fertility treatments, weight-loss pills, and erectile dysfunction meds. Everything else? That’s up to the state.

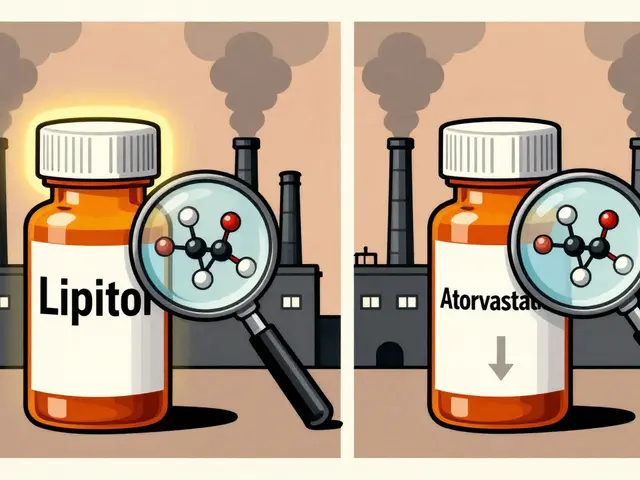

Automatic Generic Substitution: Not Everywhere

Imagine your doctor prescribes a brand-name blood pressure pill. At the pharmacy, the pharmacist hands you a generic version instead. In most states, that’s normal. In 41 states, it’s the law.

States like Colorado, New York, and Illinois require pharmacists to substitute a generic drug if it’s rated as therapeutically equivalent by the FDA. But even then, exceptions exist. In Colorado, if the brand-name drug is actually cheaper than the generic-or if you’ve been stable on it for months-the pharmacist must honor your doctor’s request to stick with the brand. Other states, like Florida and Georgia, leave substitution up to the pharmacist’s discretion, with no legal requirement to switch.

And it’s not just about swapping pills. Twenty-eight states require the pharmacist to document why they made the switch. Twelve states don’t even need to tell your doctor. That inconsistency can cause confusion-especially if your primary care provider doesn’t know you got a different pill than what was written.

Copays: From Free to $8

How much you pay at the pharmacy counter depends on where you live and how much you earn. Federal rules allow states to charge Medicaid enrollees up to $8 for a non-preferred generic drug if their income is at or below 150% of the federal poverty level. But many states go lower-or nothing at all.

In California’s Medi-Cal program, most generic copays are $1 or free. In Michigan, it’s $0 for Tier 1 generics. But in states like Alabama and North Carolina, you might pay $5-$8 for the same pill. And if you’re on a preferred drug list? Some states charge $0. Others still charge $2 or $3.

Why the difference? It’s not just about cost-sharing. Some states use copays as a tool to discourage unnecessary use. Others see them as a barrier to care. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that states with higher copays for generics also had lower medication adherence rates, especially for chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

Prior Authorization: The Hidden Bottleneck

Even if a generic is on the formulary, you might still need approval before you get it. That’s prior authorization. And it’s where the system gets messy.

Colorado’s Health First Colorado program requires prior authorization for most non-preferred drugs. For opioids, it’s even stricter: first prescription is limited to a 7-day supply, and you can’t get more than 8 doses per day without extra paperwork. Meanwhile, California’s Medi-Cal system rarely requires prior auth for generics-unless it’s a high-cost or off-label use.

Some states require step therapy: you have to try two or three cheaper generics first before they’ll approve a more expensive one-even if your doctor says it won’t work. In 32 states, this applies to drugs like antidepressants, asthma inhalers, and diabetes meds. A 2024 University of Pennsylvania study found that when Medicaid patients got switched out of their meds due to prior auth denials, hospital admissions jumped by 12.7%.

And the wait? It varies wildly. In Massachusetts, decisions come in under 24 hours. In Mississippi, it can take up to 72 hours. Meanwhile, doctors spend an average of 15.3 minutes per patient just filling out forms. That’s over $8,200 a year in lost time per physician.

Formularies: Tiered, Managed, and Confusing

Every state has a Preferred Drug List (PDL)-a tiered catalog of approved medications. Tier 1 is usually the cheapest generics. Tier 2 is brand-name or higher-cost generics. Tier 3? Often specialty drugs with strict rules.

But here’s the problem: no two states use the same list. A drug that’s Tier 1 in New Jersey might be Tier 3 in Florida. And the criteria for what makes a drug “preferred”? That’s decided by each state’s pharmacy and therapeutics committee. Some use cost alone. Others require clinical evidence, like proof that the drug works better than alternatives.

Colorado’s PDL, for example, requires patients to fail three preferred NSAIDs and three proton pump inhibitors before they’ll approve a more expensive GI drug. California doesn’t require that. The result? A patient moving from one state to another might lose access to a medication they’ve been on for years.

Who’s Running the Show? PBMs and State Contracts

Most states don’t manage their Medicaid pharmacy benefits themselves. They outsource it to Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. These firms negotiate drug prices, build formularies, and handle prior auth requests.

As of 2025, these three companies manage Medicaid pharmacy benefits in 37 states. That means a lot of standardization-but also less local control. A PBM might push a generic because it gets the highest rebate, not because it’s the best for your condition. And since PBMs are private companies, their decision-making isn’t always transparent.

Some states are starting to push back. Michigan, for example, tied its PBM contracts to outcomes: if medication adherence drops, the PBM loses money. Only nine states have tried this kind of value-based model so far. But early results show promise: one diabetes program cut costs by 11.2% without hurting patient outcomes.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Big changes are coming. In late 2024, CMS proposed a rule that would force all states to cover anti-obesity medications like semaglutide under Medicaid. If approved, it would impact nearly 5 million people. But states are pushing back-saying they can’t afford it without more federal funding.

Meanwhile, Congress is considering a bill that would stop generic drugs from qualifying for inflation-based rebates under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. If passed, states could lose up to $1.2 billion a year in rebates. That could mean higher copays, tighter formularies, or even some generics being dropped entirely.

Another shift: starting in 2025, people on both Medicaid and Medicare can switch their Part D drug plans once a month. That’s good for flexibility-but it’s also creating chaos for providers trying to keep up with dual-eligibility rules.

And supply chain issues? They’re not going away. In 2024, the FDA listed 17 generic drugs used in Medicaid as being in short supply-everything from antibiotics to seizure meds. When those run out, patients get switched to alternatives they may not tolerate.

What You Can Do

If you’re on Medicaid and rely on generics:

- Ask your pharmacist: Is this the preferred generic in my state?

- Check your state’s Medicaid website for the current Preferred Drug List. Most have searchable databases.

- If a drug is denied, ask for a medical exception. You can appeal-sometimes even with just a letter from your doctor.

- Keep a list of all your meds, including doses and why you take them. It helps when switching providers or states.

- Call your state’s Medicaid office if you’re having trouble getting refills. Some have patient advocates.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. But knowing your state’s rules gives you power. You’re not just a patient-you’re a participant in a system that’s designed to save money, but shouldn’t cost you your health.

Are all generic drugs covered by Medicaid?

No. While all states cover most generic drugs, each state maintains its own Preferred Drug List (PDL). Some generics are excluded due to cost, lack of clinical evidence, or because they’re considered non-essential. Federal law also bans coverage for certain drug types, including weight-loss medications, fertility drugs, and erectile dysfunction drugs, regardless of state.

Can I be forced to switch from a brand-name drug to a generic?

In 41 states, pharmacists are legally required to substitute a generic if it’s FDA-rated as therapeutically equivalent-unless your doctor writes "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription or if the brand drug is cheaper. Some states allow exceptions if you’ve been stable on the brand for months. Always check your state’s specific substitution laws.

Why is my generic drug not covered even though it’s on the formulary?

Even if a drug is on the formulary, you may still need prior authorization. States often require step therapy-trying cheaper alternatives first-or limit quantities based on diagnosis. Some drugs are only covered for specific conditions. Ask your pharmacy or Medicaid office for the exact reason it was denied.

How do I find my state’s Medicaid drug formulary?

Visit your state’s Medicaid website and search for "Preferred Drug List" or "PDL." Most states offer a searchable online tool. You can also call your state’s Medicaid helpline or ask your pharmacist for a copy. Some states, like Massachusetts and Colorado, have detailed PDFs with clinical criteria for each drug.

What should I do if my generic medication is discontinued or in short supply?

If your generic runs out, your pharmacist should notify you and suggest an alternative. If the alternative isn’t covered or causes side effects, ask your doctor to file a medical exception with Medicaid. Keep records of all communications. Shortages are tracked by the FDA-check their website for updates on specific drugs.

Do Medicaid copays for generics vary by income?

Yes. Federal rules allow states to charge up to $8 for non-preferred generics for people earning up to 150% of the federal poverty level. Many states charge less-$1 or $0-for low-income enrollees. Higher-income Medicaid recipients (like those in expansion states) may pay more. Always confirm your copay amount with your pharmacy before picking up your prescription.

Can I appeal a denial of coverage for a generic drug?

Yes. Every state has an appeals process. You can submit a written request with a letter from your doctor explaining why the drug is medically necessary. Many states require a decision within 72 hours for urgent cases and 30 days for standard appeals. Don’t wait-start the process as soon as you’re denied.

Next Steps: What to Watch For

If you’re managing chronic illness on Medicaid, keep an eye on two big shifts: the potential loss of inflation-based rebates for generics and the push to cover anti-obesity drugs. Both could reshape what’s available-and what you pay-for years to come.

Also, if you’re moving between states, don’t assume your meds will transfer. Even if the drug is the same, the rules aren’t. Contact your new state’s Medicaid office before you relocate. Bring your medication list, prescriptions, and doctor’s notes. It’s the best way to avoid a gap in care.

Medicaid’s generic coverage system isn’t perfect. But it’s working-for millions of people-to keep essential drugs affordable. The key is knowing your rights, your state’s rules, and how to speak up when something doesn’t add up.

Rajiv Vyas

November 29, 2025 AT 16:12Of course the government doesn’t want you to get your meds cheap-this is all a scheme to keep you dependent. They’re working with Big Pharma to make generics *look* affordable while secretly raising prices through backdoor rebates. You think Colorado’s system is bad? Wait till you see what’s happening in the shadows. The FDA? Controlled. The PBMs? Puppet masters. I’ve seen the documents. They’re replacing your pills with chalk.

And don’t get me started on the “anti-obesity drugs” push. That’s just the first step. Next they’ll ban all caffeine. Then sugar. Then breathing. You’re being prepped for mandatory health compliance. Wake up.

They’re coming for your insulin next. Mark my words.

farhiya jama

December 1, 2025 AT 15:53I literally just cried reading this. Like… why does it have to be this hard? I’m on Medicaid and I had to wait 3 weeks for my blood pressure med because of prior auth. My doctor had to call 5 times. I missed work. I’m exhausted. And now I’m supposed to ‘check my state’s PDL’ like it’s a grocery list?

It’s not a system. It’s a game no one wins. I just want my pills without the drama.

Astro Service

December 2, 2025 AT 08:32So let me get this straight-you’re mad that America lets states run their own Medicaid programs? That’s the whole point! We’re not Canada. We’re not Sweden. We don’t need some bureaucrat in DC telling Texas how to spend its money. If you want free drugs, move to Europe. But don’t cry because your state doesn’t cover your $8 generic like it’s a human right.

Also, PBMs? They’re saving you money. You’re welcome.

DENIS GOLD

December 4, 2025 AT 07:12Oh wow. A 12-page essay on how Medicaid is ‘broken.’ Wow. Groundbreaking. I bet the author got a grant for this. Meanwhile, my cousin in Alabama gets his metformin for $0 and never even heard of a ‘PDL.’

People like you make the problem worse by overcomplicating it. It’s a pharmacy. You need a pill. You get it. Stop turning healthcare into a TED Talk.

Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 5, 2025 AT 15:58My heart goes out to everyone struggling with this. I’m from Nigeria, and even here, we have drug access nightmares-but we don’t have 51 different rulebooks. What’s wild is that in the U.S., you can get a Tesla in 3 days but can’t get your antidepressant without a PhD in paperwork.

But I see hope. People like you sharing this? That’s how change starts. Keep speaking. Keep asking. You’re not alone. 💛

Daniel Rod

December 5, 2025 AT 22:46It’s funny… we spend trillions on war, but when someone needs a $2 pill to stay alive, we argue over who gets to sign the form.

What if we treated health like air? You don’t ask if someone’s ‘deserving’ of oxygen. You just give it.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the system. It’s that we’ve forgotten that people matter more than budgets. 🤔

gina rodriguez

December 7, 2025 AT 17:08Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I see this every day. One patient moved from California to Ohio and lost her seizure med. She cried in my office. I helped her appeal-and it took 11 days.

But here’s the thing: you *can* fight it. Call your state’s Medicaid helpline. Ask for a patient advocate. They’re real people who want to help. You’re not powerless. 💪

Sue Barnes

December 9, 2025 AT 17:05People who complain about Medicaid coverage are the same ones who don’t pay taxes. If you can’t afford your meds, maybe you shouldn’t have had kids. Or moved to a state that doesn’t ‘care’ enough.

Stop playing victim. Get a job. Get insurance. Or shut up.

jobin joshua

December 10, 2025 AT 10:31Bro… I just tried to get my generic lisinopril in Delhi and they gave me a different brand. I didn’t even ask. They just said ‘same thing.’ I looked up the code-same active ingredient. Same batch. Same everything.

So why is the U.S. making this so hard? 🤨

Sachin Agnihotri

December 10, 2025 AT 15:12Wait-so if I’m on Medicaid in Texas and I move to Oregon, my diabetes med might suddenly be ‘non-preferred’? That’s insane. I’ve been on the same drug for 7 years. I didn’t sign up for a pharmacy lottery.

Also, why does every state have a different name for the same list? PDL? Formulary? Preferred Drug Schedule? Just call it ‘the list’ and be done with it.

…I’m just asking for clarity. Is that too much?

Diana Askew

December 10, 2025 AT 15:42Of course the government is hiding something. Why else would they let PBMs run everything? CVS Caremark? That’s the same company that sold opioids to towns while pretending to be a ‘healthcare provider.’

They’re not ‘saving money’-they’re stealing it. And you’re all just too lazy to see it. The FDA is in their pocket. The doctors are paid off. Even your pharmacist is in on it.

Check your pill bottle. The logo? That’s not a logo-it’s a mark of control.

Yash Hemrajani

December 12, 2025 AT 00:50Look, I’ve worked in pharma for 15 years. The real issue? The rebate system is backwards. PBMs get paid more the more expensive the drug is-so they push higher-cost generics even when cheaper ones work.

It’s not about state rules. It’s about profit. The system rewards complexity. That’s why your $1 generic gets denied and your $8 one gets approved.

Fix the rebate. Everything else follows.

Pawittar Singh

December 12, 2025 AT 09:59Hey everyone-don’t give up! I know it feels like the system is rigged, but I’ve helped 3 people in my neighborhood get their meds approved just by calling Medicaid and asking for the ‘medical exception form.’ It’s not easy-but it’s possible!

Bring your doctor’s note. Write ‘URGENT’ on the envelope. Follow up every 2 days. You’re not a burden-you’re a warrior. 💪❤️

And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? You’re not alone. I’ve been there. We got this.

Josh Evans

December 14, 2025 AT 06:58I’m from Ohio and my copay’s $8. I know it’s high. But I also know that if we made it free, the state would just raise taxes. This is the compromise. Not perfect. But better than nothing.

Also-did you know 90% of people on Medicaid don’t even pay copays? Most are under 150% FPL. So yeah, the $8 is for the few who can afford it. It’s not a punishment. It’s a buffer.

Allison Reed

December 15, 2025 AT 13:40Thank you for the detailed breakdown. This is exactly the kind of clarity people need when they’re overwhelmed. I’ve shared this with my community group. We’re organizing a workshop on how to navigate formularies next month.

Knowledge is power-and you just gave us a map.

Jacob Keil

December 17, 2025 AT 08:54the system is broken becuz its run by corprations and politicians who dont care about people. they just want to make money and look good. its not about health its about control. you think they want you to be healthy? no. they want you to be dependant. the pills are the leash. 🤡